David Goodhart responds to NIESR Director Jonathan Portes’ review of his book “The British Dream”

[UPDATED 9 JULY WITH A FURTHER ROUND, at bottom of page]

[UPDATED 9 JULY WITH A FURTHER ROUND, at bottom of page]

My long review of David Goodhart’s book on UK immigration, “The British Dream”, appeared in the London Review of Books last week. David has written to the LRB in response, and I have replied – this exchange will appear shortly. However, David’s response was constrained by the LRB word limit, while mine was rather rushed. So I agreed to post his response here in full, unedited, and have expanded mine somewhat in response. Here they are.

David’s full letter to the LRB in response to my review:

Jonathan Portes, as readers of this blog know very well, leads one of Britain’s most respected economic think tanks. So when he pronounces on the economic effects of mass immigration, as he did in his polemic about my book The British Dream in the last edition of the London Review of Books, one should listen.

But one should also be on guard when he tries to pass himself off as a neutral expert, drawing his views objectively from an academic consensus. First, there is no deep consensus on this issue. Second, Portes is a partisan here, well known in the New Labour era as the Whitehall economist most in favour of as much immigration as possible.

His piece was not a conventional review, my book ranges over, among other things, the history of post-war immigration, the multiculturalism story, national identity, and the progress of Britain’s ethnic minorities, none of which Jonathan addresses while spending a significant part of his critique on the issue of social mobility which takes up just half a page of a 416 page book. Rather his piece is a narrowly focussed defence of his own passionately held belief that a rising tide of mass immigration “lifts all boats.”

Both Portes and I accept that most of the economic literature concludes that large scale immigration makes surprisingly little difference to growth (measured properly), incomes, employment and so on. But he then (like many economists) accentuates the positive, stressing the boost to incomes at the higher end of the spectrum and the hard to measure dynamism immigration creates, and I (along with many other economists) stress the negative, the downward pressure on wages, the job displacement and employer short-termism/disincentive to train.

According to the ONS 20 per cent of low skilled jobs in Britain are taken by people born abroad. Moreover, between the end of 1997 and 2011 2.7m more people were employed in Britain, 2.1m of whom were born outside the country. Of course there is no fixed lump of labour, many newcomers fill jobs that are complementary to existing workers and some of those jobs would not have been created at all if the outsiders had not turned up. And, of course Jonathan is right, even with no immigration the hard to employ in almost completely indigenous former industrial areas like Barnsley would remain hard to employ.

But it is surely dogmatism to argue, as Jonathan appears to, that the “lump of labour fallacy” means there is no displacement or discouragement of resident British workers as a result of immigration: what one might call the opposite “no displacement fallacy.” As the top economists at the government’s Migration Advisory Committee agree, there is clearly some trade off between immigration and opportunities for domestic labour especially in a weak labour market with competition from often better motivated foreigners with lower wage expectations, which raises issues about the country’s social contract with its poorer citizens.

The proper use of data is central to this debate but it is also not enough to sit in central London looking at databases, you also have to talk to real people. The immigration story is not only an economic cost-benefit analysis it is also about human experience and emotion, about communities and neighbourhoods and the pace of change. And evidently non-British net immigration of around 4m in just 15 years has represented too much change for many people.

I tried to capture some of this in my book, too, in, for example, my pen portrait of the London borough of Merton. I spent some time there and spoke to many people one of whom (a local councillor) mentioned to me the relatively high number of young white British NEETs (people not in education, employment or training). I did not check the number, which Jonathan says is in fact quite small.

But the main point here is that a single NEET figure does not invalidate the bigger story I was trying to tell about an area which though not as troubled as, say, Barking and Dagenham has nonetheless left many white people feeling out of place as the minority population has grown from virtually nothing to over half in 30 years. Telling such people that they are fortunate to live in a more dynamic place than immigrant-free Hartlepool is not an adequate response.

I cannot be so magnanimous about Jonathan’s reflections on Bradford. Here, the supposedly rigorous social scientist launches a moralistic attack on my own account based on one anonymous quote and a single misleading statistic! My source for the fact that Bradford has just opened two more special schools is Cllr Ralph Berry, Labour chair of the education committee.

And while it is true that Bradford is only slightly above the national average of those who qualify as having SEN (special educational needs) there are other forms of “special help” which push the numbers up. One of the main authorities on cousin marriage within the Pakistani community in Bradford is a woman called Nuzhat Ali who told me that almost 30 per cent of Pakistani children suffer from mild or severe disability as a result of cousin marriage adding “that almost half have special needs at school.” Even if this is an overestimate, and it is not clear that it is, Nuzhat is bravely opening an important debate and Jonathan should not be trying to close it down.

One of the big advances in the immigration debate in recent years is that we have been able to separate questions of racial justice from questions about the economics of immigration. With his highly emotional language—his talk of my “dangerous” and “alarmist” arguments and his accusation of “scapegoating”—Jonathan is trying to weld them back together again in order to make his case to the LRB’s mainly left liberal readers.

The other point on which he cannot see the bigger picture is integration/segregation. The picture here is very mixed but he chooses to present only the welcome evidence of mixing and dispersal. Yet work on the 2011 census by Eric Kaufmann of Birkbeck College has found that 41 per cent of ethnic minority Brits now live in wards which are less than half white British often much less, and that figure has risen from just 25 per cent in 2001.

Finally, Jonathan accuses me of not dealing sufficiently with the positive case for immigration. But my skeptical arguments are aimed mainly at liberal Britain where I can take the positive case for granted. Also, this is not an argument for or against immigration it is an argument about scale. Most of the dynamic benefits that Jonathan and others point to can still be achieved at the “tens of thousands” level that the current government is aiming for; and that Jonathan believes is a big policy mistake.

The sub-title of my book is “successes and failures of post-war immigration” and it tries to take an unsentimental look at the immigration story over the past 60 years. It is not a radical book, and its main conclusions on current policy issues can be summarized in one sentence. Britain should return to more moderate levels of immigration given the lack of significant economic benefit to the existing population, especially in the bottom part of the income spectrum; we should celebrate more what an open country we have become as a glance at the outcomes for many of Britain’s biggest ethnic minorities makes clear, but we should also worry about the “parallel lives” problem in many parts of the country and the lack of a common life across ethnic boundaries. Such mainstream views can only be alarming to people who live in academic or ideological bubbles.

Jonathan’s free market social liberalism – what the Americans call “Woodstock and Wall Street”— is well represented in the public domain, perhaps he would allow my social democratic skepticism about large scale immigration a place too without calling me “dangerous.”

My reply

Perhaps the central point of David’s response is this:

The proper use of data is central to the debate but it is not enough to sit in Central London looking at databases….you also have to talk to real people.

But what does that really mean? In my review, I questioned the accuracy of two statements. The first was about Merton:

[Poor whites have] mainly opted out: they seldom vote, and a lot of the younger people are “Neets” – not in employment, education or training.

David, in his response:

I spent some time [in Merton] and spoke to many people one of whom (a local councillor) mentioned to me the relatively high number of young white British NEETs (people not in education, employment or training). I did not check the number, which Jonathan says is in fact quite small.

Second, on Bradford:

On some measures nearly half of all children in [Bradford] qualify for special help

David, in his response:

One of the main authorities on cousin marriage within the Pakistani community in Bradford is a woman called Nuzhat Ali who told me that almost 30 per cent of Pakistani children suffer from mild or severe disability as a result of cousin marriage adding “that almost half have special needs at school.” Even if this is an overestimate, and it is not clear that it is, Nuzhat is bravely opening an important debate and Jonathan should not be trying to close it down.

In other words, in both cases, by his own admission, David reported vague and unsubstantiated statements by individuals as fact. With no source, the reader is implicitly expected to trust that the author has done his homework. But as it turns out, those statements (at least in the form he reports them in the book) were incorrect. In both cases, David could easily have checked and reported detailed official statistics, but he chose not to do so.

Nor are these isolated examples, as David implies. The book is littered with examples of unsourced “facts”. Most are probably accurate. But some important ones are not. To take one particularly egregious example, in a book that argues that the last Labour government touched off “the second great wave of post war immigration”, David states (page 161), as fact, that immediately prior to the 1997 election “even the gross annual inflows were only about 50,000”. This is wrong by a factor of about 5; the correct figure is closer to 250,000. I don’t think here even David would use the “somebody I met told me and it sounded plausible” excuse.

More broadly, David’s problem is that he wants to have it both ways. He wants his book to be taken seriously as research – in his reply to Diane Abbott, he said:

I have just written a 400-page book about postwar immigration to Britain. It is crammed with facts and figures.

But on the other hand, he doesn’t want to actually take the trouble to observe even the most basic disciplines that apply to research – or even to journalism – and, as a consequence, makes numerous mistakes. The result, as my review pointed out, is a mess – a book that is indeed crammed with facts and figures, but where the reader can have absolutely no confidence that any specific fact or figure is reliable.

So let us be clear. This is not about whether “talking to real people” is useful, or about facts versus perceptions. It is about the simple fact that David, by his own admission, did not do his homework (and that his publishers, to their discredit, allowed him to get away with it).

This lengthy discussion should dispose of any remaining shred of credibility of “The British Dream” as research or analysis (interesting and informative as it often is as social observation, as my original review said). But that doesn’t mean all David’s arguments are necessarily wrong, so let me move on to substance. Here his response is much more measured and coherent than the book. One of my main points was the contradiction between his reasonable discussion of the evidence on economics and integration, on the one hand, and his unsubstantiated and alarmist talk of “Saudi Arabianisation” and “little Somalias”, on the other. His response reflects the former approach and does not attempt to defend the latter. I will take that as concession rather than rebuttal.

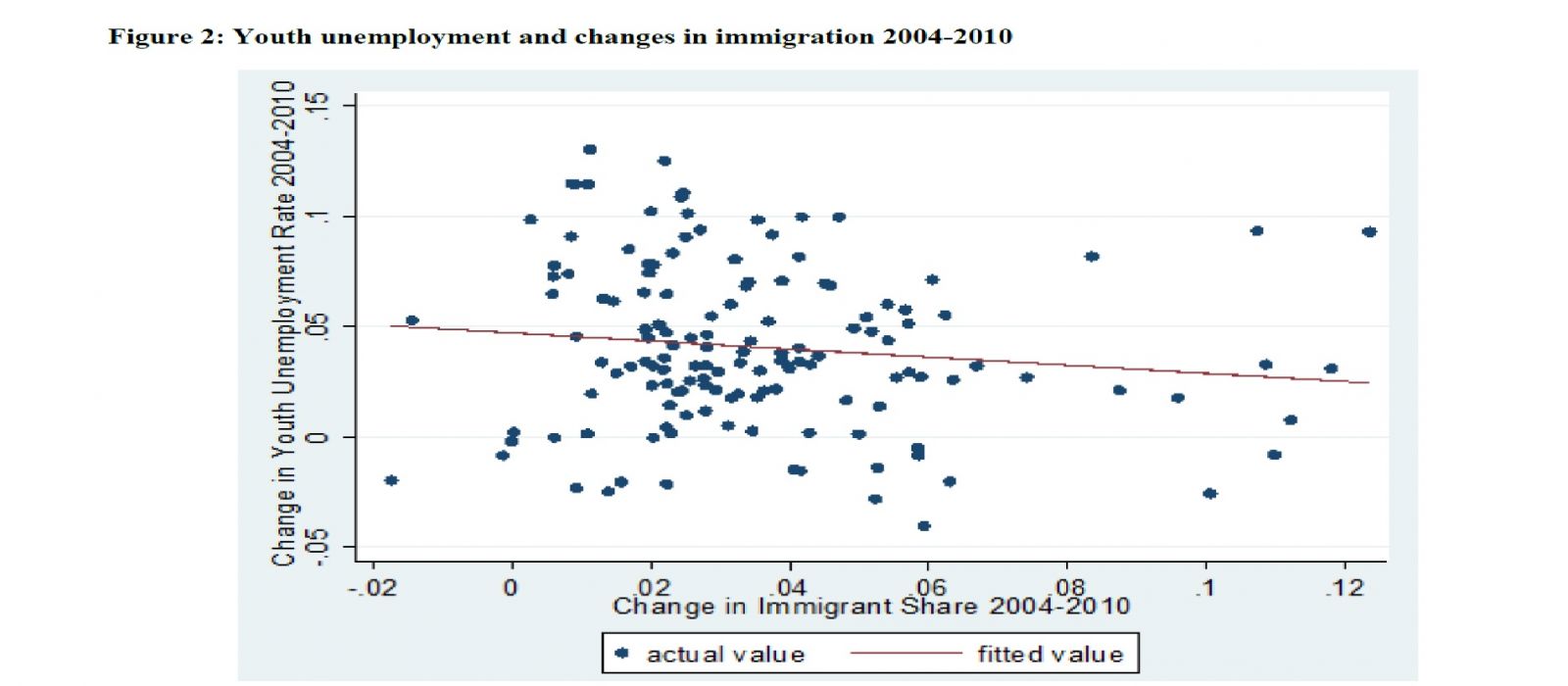

In particular I think he recognises that whatever the perceptions, in Merton or anywhere else, there is little or no evidence that immigration has made more than a marginal contribution to reducing educational or labour market opportunities for less advantaged Britons. Indeed, those opportunities are frequently worse in areas with very low immigration. Ironically, David refers to the “top economists at the Government’s Migration Advisory Committee (MAC)”, and implies that they have a different take on these issues than I do. But this argument, set out in more length and with evidence in my review, is precisely that made out by Jonathan Wadsworth, MAC member and Professor of Economics at Royal Holloway, who points out

native born youth unemployment rose less in areas that experienced a larger change in the share of immigrants.

Perhaps his book should have mentioned this. He could even have reproduced Jonathan’s helpful chart, which makes my point, rather than repeating the vague and inaccurate statement about NEETs in Merton discussed above. The rest of Jonathan’s excellent summary of the research evidence, here, is also of course far closer to my view of the evidence than David’s.

Similarly, David refers to “minority clustering”. Let’s be clear what he means by this; areas where more than half the population is not white British. For example, my home borough of Islington, which is now 48% White British, 20% White “other” (including Irish), 13% Asian, 9% black, and 6% mixed. According to David, this means there is “less opportunity for interaction with the white mainstream.” Islington certainly has its problems. Lack of inter-ethnic interaction is not obviously one of them.

More generally, David doesn’t try to claim that there is actually any increase in minority segregation as normally defined; on this, he does understand the data. He simply thinks that areas with lots of “minorities” are somehow problematic, whether those minorities are French academics, retired Americans, British Asians, or the mixed progeny of any of the above with “white British”. Maybe they are. But he doesn’t really explain how or why.

All this is a start on the way back to a sensible, evidence based discussion. If David were to produce a new edition of his book, errors corrected, properly sourced and comprehensively fact-checked, it might actually be a useful contribution, although there would of course be lots I’d still disagree with.

Finally, I will deal only briefly with the more ad hominem aspects of David’s response. I suspect he is well aware that there is a difference between saying, as my review did, that a book that doesn’t bother to get its facts right is not a useful contribution to debate, and trying to “close down” that debate. Equally, he suggests that my use of language like “dangerous” is “highly emotional”. Nowhere does my review argue that any of the subjects David covers are dangerous. They are, however, sufficiently important and sensitive that his slapdash (at best) approach to evidence and analysis is exactly that.

David’s further response in full

Jonathan Portes says my 900 word letter in the last LRB is more “coherent” than the 416 page book I wrote ranging over a large number of subjects related to post-war immigration and its management. But this is apples and pears. You cannot judge a book like The British Dream by the standards of a specialist academic paper. There are a very small number of factual errors in the book which I will correct, none of them have any bearing on the book’s main arguments. In the few cases where the detail is wrong (or more often unclear) the bigger point remains correct: whether it is the worrying level of genetic disability deriving from cousin marriage among British Pakistanis in Bradford and the knock-on effect in schools or the very significant increase in the level of British immigration (both net and gross) after 1997. Does Portes deny either of these?

Portes sniffily rejects my use of the terms “Saudi Arabianisation” and “little Somalias”. Saudi Arabianisation is a metaphor. I do not mean that our labour market has literally become like Saudi Arabia’s, but in some parts of the country too many British citizens are “parked” in unemployment or inactivity while newcomers with lower wage expectations fill many of the low skill jobs. And, of course, Somalis cluster together (often in social housing) in many parts of the country, as minority groups always have done at least initially. If Portes went to parts of Leicester or west London he would hear people talking about “little Somalias” including the Somalis themselves.

As the last example illustrates my book includes a fair amount of reporting and listening to people as well as sifting through the numbers and the literature. Many of the unsourced facts that Portes complains about come from relevant local experts such as Councillor Ralph Berry, Labour head of the Bradford education committee, who does not regard what I have written as “alarmist.”

Portes was one of the architects of Labour’s immigration policy and has to defend it against my critique. He claims that I am wrong to want to return to net immigration of around 100,000 a year but where is his evidence of the economic benefit to existing citizens in the bottom half of the income spectrum from the much higher levels of recent years? And what about the worrying evidence for continuing “parallel lives” in some parts of the country? Instead of responding to the main challenges set down in my book Portes has just been sniping in the footnotes.

My further reply

“So “The British Dream” contains “only a small number of factual errors”. How would David Goodhart know, when, by his own admission he doesn’t check facts or cite sources? As I have pointed out to him, the discussion of the US welfare state contains three factual errors on a single page (page 265).

Luckily these errors “have no bearing on the main arguments” in David’s view. That begs the question of why David discusses subjects of which he’s ignorant. But his central theses are also full of holes.

He refers to “worrying evidence” for “parallel lives”. To support this he has repeatedly, most recently in the FT and in a video for the Guardian (when incidentally he managed to get his immigration statistics wrong again), claimed that the number of “white British” people leaving London tripled between the 1990s and the 2000s. He argues that this “extraordinary movement” is strong evidence of “white flight” – a phrase he is single-handedly attempting to introduce to the UK debate. Except that the 1991 census he cites did not include a “white British” category; he’s comparing two different numbers that are not, in fact, comparable. His source? Professor Erik Kaufmann, of Birkbeck College, who is indeed a respected expert in this area. But when asked to confirm the numbers, Professor Kaufmann responded publicly “Will know firm numbers soon. But there isn’t “white flight”” – thus contradicting both David’s numbers and his interpretation. .

As my original review made clear, I am basically sympathetic to David’s views on the importance of integration. But anyone who wants any actual evidence, worrying or otherwise, as opposed to misleading and alarmist misinterpretation, should go elsewhere.

Meanwhile, when it comes to the labour market, he defends his use of the phrase “Saudi Arabianisation” as just a “metaphor” – presumably because, as my review also showed, he ran out of evidence, accurate or otherwise, to worry about.

If these issues didn’t matter, the sheer amateurishness of “The British Dream” would be comical. But they do, so my verdict of “dangerous” still stands. “