Independent Scottish Government Borrowing Costs: A Reply

Our estimates of the possible borrowing costs for an independent Scottish government contained in full detail in our Discussion Paper 416, Scotland’s Currency Options, have been closely examined by all sides of the debate. In recent weeks Professor Andrew Hughes-Hallett, a member of the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Commission Working Group and Council of Economic Advisors, in evidence to the Scottish Parliament, claimed that:

Our estimates of the possible borrowing costs for an independent Scottish government contained in full detail in our Discussion Paper 416, Scotland’s Currency Options, have been closely examined by all sides of the debate. In recent weeks Professor Andrew Hughes-Hallett, a member of the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Commission Working Group and Council of Economic Advisors, in evidence to the Scottish Parliament, claimed that:

1. The estimates are too high, because they abstract from currency risk

2. The estimates do a poor job of in-sample forecasting, in particular for Austria.

Since these claims were made at a public evidence session, we would like to reply in public to each claim. This is a largely technical note to clarify these issues.

Currency risk

Prof. Hughes-Hallett claims that the estimates of Scotland’s borrowing costs are too high, because they abstract from currency risk. He says (Scottish Parliament, 2014):

“Unfortunately, because of the way that the institute ran its analysis, the paper includes explanatory variables to tell you how the risks work only from the debt and deficit side—there are none from the fiscal side. The institute does not worry about the currency risk side, which means that those variables have to work twice as hard in order to explain both parts, which gives an exaggerated effect. That is a problem.”

The goal of our model was to estimate the borrowing costs for an independent Scotland within a monetary union with the rest of the UK. This is the Scottish Government’s proposal in its White Paper. We suspended our doubts about how robust this monetary union would be, and simply assumed for the moment that there was full political commitment on both sides and for all time to make this work. As there is obviously no data for a possible independent Scotland’s borrowing costs within a monetary union (which we will call here the ‘Sterling-zone’), we used data from another monetary union, the Euro-zone, from 2000 to 2012 to estimate differences in borrowing costs between countries of different characteristics.

The whole point of using data from the European monetary union is to abstract from currency risk. There is full political commitment from all members of the Euro-zone towards the union (despite some extraordinary economic conditions). Indeed, there is no provision or mechanism for a country to leave the Euro even if it had wanted to do so. One could perhaps argue that over the whole sample period there was a remote and temporary possibility of one or two countries leaving during the darkest days of the crisis. It was precisely for this reason that we added dummy variables to the model for crisis countries in that period to capture any possible currency risk. Therefore, we are content that the model is purged of possible currency risk.

It is not clear to us how (or why) one could ever try to capture currency risk as distinct from credit risk within a monetary union, where there are no separate currencies, no mechanism to exit the union and no political will to do so. Not taking non-existent currency risk into account cannot therefore bias our estimates of borrowing costs.

However, now the point has been raised, it is worth stating how currency risk may influence the spread of borrowing costs between an independent Scotland and the UK in a non-robust Sterling-zone. When we estimated our spreads we assumed that there would be full commitment to the monetary union to be conservative. However, this is less clear today. The Scottish Government has already indicated that there exists an exit clause (see page 111 in the White Paper) and it appears that support for a monetary union if Scotland were to become an independent nation is not unanimous. If there is currency risk this would change the spread of borrowing costs between the UK and an independent Scotland.

Would Scottish borrowing costs be even higher or lower than our original estimates? The uncertainty accompanying any expectations that the currency union might break up would tend to generate a currency risk premium for lenders outside of Scotland, leading to higher Scottish borrowing costs. In addition, if one assumes that upon leaving the Sterling-zone an independent Scottish currency would in fact be stronger than Sterling then the spread would be narrower. On the other hand, if one assumes that an exit would be followed by the introduction of an independent Scottish currency that would be weaker than Sterling, then the Scottish government’s borrowing costs would be higher than we estimated. Very few countries elect to leave currency zones when they are enjoying success.

In-Sample Forecasting

Now let’s turn to Prof. Hughes-Hallett’s second assertion about the ability of our model to adequately fit the data on Eurozone borrowing costs. He says (Scottish Parliament, 2014):

“For example, Austria’s ratios to Germany are exactly the same as Scotland’s ratios to the rest of the UK, almost to the percentage point. The model predicts a risk premium of 4 per cent for Austria, but it is actually 0.4 per cent at the moment—so the prediction is 10 times wrong, if I can put it that way.”

This is incorrect. Our model predicts that Austria’s average spread over Germany’s 10 year bond yields for 2000-12 should be -0.27 percentage points, while the actual average spread for this time period was 0.33 percentage points. So far from overestimating Austria’s spread by a factor of ten, our model, when applied correctly, underestimates it by 0.60 percentage points. Table 1 gives details on how the estimated spread for Austria has been calculated.

Table 1: Calculating in-sample forecast for Austrian average 10 year bond spreads

|

Coefficient Name |

Estimated Coefficient |

Austria |

Contribution to Spread |

|

Constant β0 |

-2.0000 |

-2.0000 % |

|

|

Debt-GDP β1 |

0.0023 |

-0.220 |

-0.0005 % |

|

Deficit-GDP β2 |

-0.5085 |

-0.055 |

0.0280 % |

|

Tax Volatility β3 |

6.4887 |

0.002 |

0.0156 % |

|

Liquidity β4 |

-3.5247 |

-0.230 |

0.8110 % |

|

Business Cycle β5 |

2.0074 |

0.000 |

0.0000 % |

|

Crisis β6 |

3.3136 |

0.000 |

0.0000 % |

|

World β7 |

0.2292 |

2.105 |

0.4825 % |

|

Crisis*Debt-GDP β8 |

1.0003 |

0.000 |

0.0000 % |

|

Crisis*Deficit-GDP β9 |

0.1094 |

0.000 |

0.0000 % |

|

Ave Time FE β10,t |

0.4352 |

0.4352 % |

|

|

Total |

-0.2281 % |

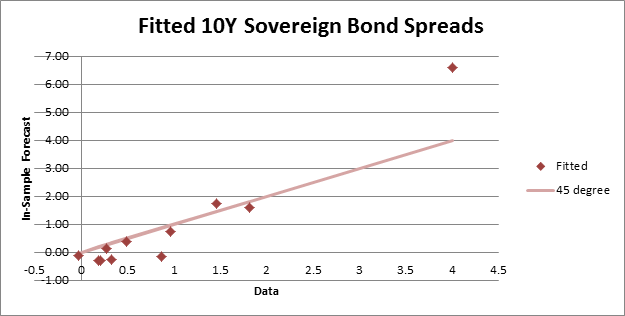

Austria is no exception. With the exception of the crisis countries Greece and Ireland, the model tends to underpredict the actual borrowing costs. The scatter plot in Figure 1 below illustrates the point graphically. The horizontal axis gives the data values for the average 10 year government bond spreads – the difference in 10 year bond yields to Germany, while the vertical axis gives the model prediction. Any points which lie above the 45 degree line are over-predictions, while any points below the 45 degree line are under-predictions.

The tendency to underestimate for non-crisis countries, but to overestimate them for crisis countries has two implications. First, it would indicate that the model tends to underestimate borrowing costs for non-crisis countries. Second, it would indicate that there is something about the high borrowing costs for crisis countries that our model does not capture, despite trying to account for Crisis using a dummy variable that was turned on whenever GDP fell by more than 5% on an annual basis.