Welfare reform and the “jobs miracle”

The recent performance of the UK labour market since the financial crisis has astonished almost everyone. Employment did not fall nearly as much as might have been expected, given the size of the contraction, and the subsequent period of stagnation. And when it started growing again it grew much faster than expected. The overall employment rate is now back more or less at its previous peak (in early 2005) and may well rise even further.

The recent performance of the UK labour market since the financial crisis has astonished almost everyone. Employment did not fall nearly as much as might have been expected, given the size of the contraction, and the subsequent period of stagnation. And when it started growing again it grew much faster than expected. The overall employment rate is now back more or less at its previous peak (in early 2005) and may well rise even further.

What explains this? Most analysis so far has focused on both the upsides and downsides of the flexible labour market that labour market and welfare reforms have created over the past 30 years, under governments of both parties. Lots of jobs are being created and unemployment is much lower as a consequence, but both productivity and wages have been exceptionally weak, and much of the new employment is “insecure” (zero hours contracts, or low productivity self-employment). I have argued that the glass is (at least) half full – better an insecure job than no job – although there’s plenty to worry about.

However, others have sought to find a different explanation, related to much more recent government policy. The claim is that the “British jobs miracle” is not the payback for incremental reforms introduced over a very long period, but rather attributable to the much more recent “welfare reforms” introduced by Iain Duncan Smith. The clearest exposition of this thesis is given by Fraser Nelson here:

There has clearly been a game-changer, something that none of the economists had incorporated in their models. And senior figures inside the Bank are beginning to conclude (and openly hint) that this is Iain Duncan Smith’s welfare reforms. What confounded the eggheads was that the number of workers is growing four times faster than the number of working-age people: in other words, Britons have become far more likely than pretty much anyone else to look for –and find – work. Why? It’s hardly the dazzling salaries on offer, since wages are still being outpaced by inflation. Nor is it immigration: that’s still continuing, but the dole queues are shrinking faster. Fewer people now claim the three main out-of-work benefits than at any time during the Labour years.

Others (for example Roger Bootle here) have endorsed this position. Now, Chris Dillow (and others) have pointed out the path of employment was perfectly consistent with the observed fall in real wages. But, as Chris admits, that doesn’t mean “welfare reform” (now or previously) wasn’t part of the story – simply that the channel through which welfare reform worked to raise employment was via lowering real wages (rather than, say, increasing “employability”).

But in fact we can assess the impact (or otherwise) of recent welfare reforms, at least at a high level much more directly. Fraser has previously argued that

And mass immigration allowed Brown to grow the economy without fixing welfare. It broke the link between more jobs and less dole.

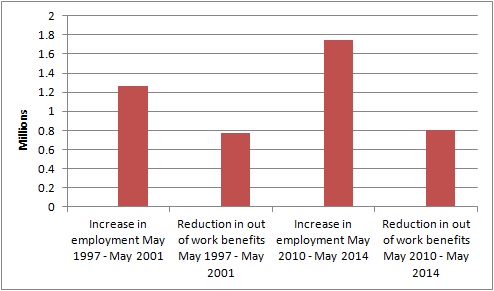

So, presumably, he now thinks that fixing welfare has restored the link between “more jobs and less dole”, and this explains the “jobs miracle”. What does the data actually say? This very simple chart shows the growth in employment (for those of working age) and the reduction in the numbers on out of work benefits for two periods – May 1997 – May 2001, and May 2010 – May 2014.

If the recent increase in employment was more closely related to moves off benefit than previously, you’d expect to see a closer relationship between the two figures. But that’s not what it shows. In fact, the reduction in out of work benefits (“dole”) was much the same in the two periods, but job growth was greater in the more recent one. In other words, a somewhat smaller proportion of the recent increase in employment was accounted for by a reduction in those on benefits than in the earlier period. I’ve tried looking at this split with different sub-periods, or on a rolling basis, and though the numbers move around, the conclusion is the same. The link between “more jobs and less dole” is there, but it’s not one-for-one, and, crucially for Fraser’s thesis, it hasn’t been “restored” – if anything it has weakened. So Fraser’s thesis simply falls at the first hurdle. The numbers simply don’t support it.

What about Fraser’s reference to the Bank of England? Surely they wouldn’t endorse this hypothesis without any evidence? Here’s the exact quote:

Higher transition rates out of longer-term unemployment had suggested that those affected might have retained a greater attachment to the labour market than had been feared. A tightening in the eligibility requirements for some state benefits might also have led to an intensification of job search.

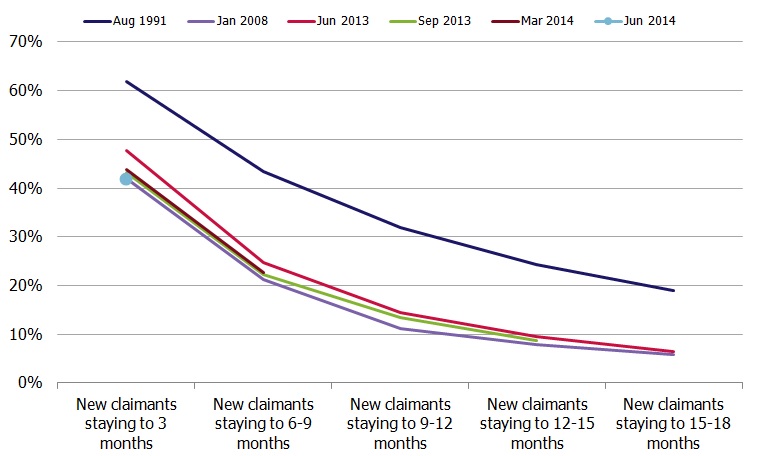

Again, we can look at the figures. Inclusion produce a useful chart each month analysing “off-flow rates” – how long people stay on Jobseekers Allowance.

It shows pretty clear that things did improve – a lot – between 1991 and 2008. Then they deteriorated slightly during the recession, and have since mostly recovered. But the idea that those on JSA are getting job more quickly than before the recession – let alone that recent “welfare reform” has anything to do with it – has no support in the data.

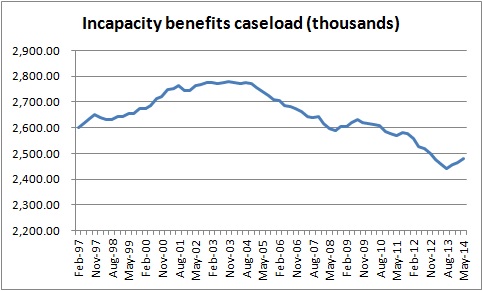

Of course, most people on out of work benefits are not on JSA. And the lack of impact of recent “welfare reform” is particularly noticeable in the case of the largest single benefit – Employment and Support allowance (previously Incapacity Benefit).

The caseload began to fall, slowly and steadily, in 2004 or so, reflecting both changes to the benefit and demographics. It rose slightly during the recession, but then resumed its fall at roughly the same pace, until recently when it began to increase again slightly. This recent reversal of historic trends is almost certainly the result of the administrative chaos surrounding the ATOS contract for the Work Capability Assessment. In other words, to the extent that “reform” has had any impact on the benefit caseload recently, it’s been to increase it.

What about the long-term unemployed and others who have been on benefit for extended periods? The government’s flagship “reform” in this area is the Work Programme, on which the NAO recently published a detailed report:

After a poor start, the performance of the Work Programme is at similar levels to previous programmes but is less than original forecast. The Department has struggled to improve outcomes for harder-to-help groups. The Programme has the potential to offer value for money if it can achieve the higher rates of performance the Department now expects.

Now this is a preliminary assessment, not a proper impact evaluation. But, if correct, it suggests that as yet the impact of the Work Programme on long-term benefit receipt has been minimal (at best), although it might improve in the future.

Does all this mean “welfare reform” has not made a difference? Absolutely not. As I say above, I and most labour market economists believe, and the evidence shows, that changes over the past 30 years have improved the functioning of the UK labour market in many respects. And, in particular, both this government and the previous one deserve considerable credit for not repeating the disastrous mistakes of the past – which saw the number of people on out of work benefits soar from about 2 million in 1979 to almost 6 million in 1994. But this has little or nothing to do with new “reforms” introduced under this government.