Worrying about the US inflation outlook

In October 2021, the US 12-month CPI inflation rate reached its highest level in the US since 1990, 6.2 per cent year-on-year. Pent-up demand and higher energy prices have been a major factor in the increase but supply chain shortages and increases in other commodity prices also explain more recent increases (see Sanchez Juanino, Macchiarelli and Naisbitt, 2021). A key question of policy debate is whether the increase in US inflation will be just temporary, as in 2008, the start of a prolonged period of inflation above the 2 per cent target, or worse still whether inflation will continue to escalate as it did in the 1970s and early 1980s.

As this year has passed, the Federal Reserve has revised up its projections for annual inflation for both this year and next. For PCE inflation, the September median projection for year-on-year inflation in the fourth quarter increased to 4.2 per cent for this year and 2.2 percent for next year. Both projections are higher than those made in March: 2.4 per cent for 2021 and 2.0 per cent for 2022. While the projections have increased, Federal Reserve members continue to expect that inflation will fall sharply next year. At its November meeting the Federal Open Markets Committee announced that it would reduce its monthly purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities in a policy known as tapering. But it continued to stress that it felt that the rise in inflation was largely transitory, as reflected in its inflation projections.

While we too expect inflationary pressure to moderate, we are concerned that the fall may not be substantial. The National Institute’s Autumn Global Economic Outlook (2021) predicted that annual US PCE inflation would rise from 1.2 per cent in the fourth quarter of last year to 5.1 per cent this year and moderate to 2.3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022. However, we see risks as mainly skewed on the upside: should these risks materialise they will force the Federal Reserve to dial monetary policy back earlier than it appears to be planning.

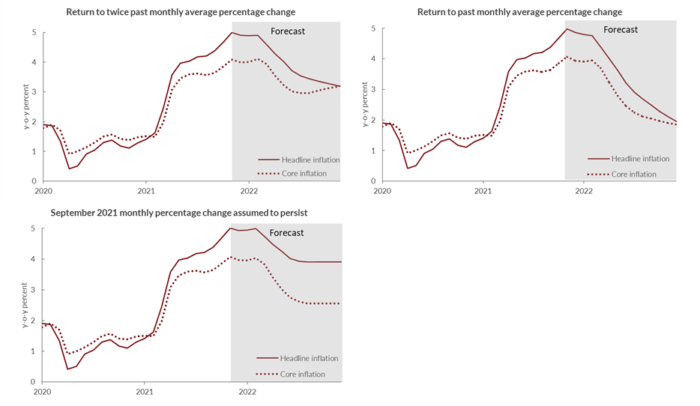

To illustrate the risks, we use the approach used by Dixon (2021) which allows us to make stylised assumptions about future monthly price changes to derive possible paths for annual inflation over the next 18 months. In particular, we look at three scenarios (rather than forecasts).

In the benign case, we assume that monthly inflation falls gradually to return to the average for the five years before the pandemic in June next year and then holds there. The monthly price changes are then translated into year-on-year inflation. On this basis, annual PCE inflation next year would fall to 2.1 per cent in the final quarter of next year, close to the Federal Reserve’s median projection.

We examine two other scenarios which are even less comforting. We assume that the size of monthly price increases falls but does not reduce as quickly or as far, so that it reaches twice the pre-pandemic period average next June. In this case, annual PCE inflation would average 3.2 per cent in the final quarter of next year.

Finally, if monthly PCE inflation holds at the latest monthly increase (of 0.3 per cent) through next year, annual inflation in the fourth quarter of next year would be 3.9 per cent. The scenario projection paths for year-on-year inflation are shown in figure 1.

The most interesting feature of these scenarios is that all three point to annual inflation staying close to 5 per cent in the next few months. The implied paths for year-on-year inflation in figure 1 show that even with monthly inflation dropping back to the 2015-2019 average by next June, year-on-year inflation continues rising for the next few months, hitting 5 per cent, as the smaller monthly increases in the latter part of 2020 are replaced by larger monthly increases this year. Year-on-year inflation only returns to 2 per cent at the end of next year in the benign case. If monthly inflation remains at 0.3 per cent a month, year-on-year inflation remains stubbornly close to 4 per cent.

These are simply projections based on stylised assumptions, rather than forecasts or a detailed analysis of the underlying factors behind recent and prospective monthly price changes. They are broadly consistent with a view that even if the current increases in prices that are due to supply chain disconnections fade away over time, annual inflation risks will stay elevated through 2022. The situation could worsen if policies do not prevent a build-up of inflation expectations.

Figure 1 Projected year-on-year PCE inflation based on stylised monthly assumptions (per cent)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis databank and authors’ calculations

The Federal Reserve is likely to increase its own inflation projections next month, but its important task is to ensure that, in a time of increasing inflation, it does not lose the credibility it has gained over the years for its efforts in keeping inflation close to its 2 per cent target.

With its new mandate and a clear focus on maximum employment, the Federal Reserve is prepared to have a temporary (or, in the current jargon, transitory) inflation over-shoot, particularly as this comes after a prolonged period of undershooting its target. The risk is that a transitory over-shoot might develop into a prolonged over-shoot if inflation expectations become unhinged and wage-push inflation factors mount.

Judging by our scenario projections, the present inflation rate could return towards its target rate by the end of 2022. However, it seems more likely that inflation may continue to overshoot target for some time. If inflation hits 5 per cent the Federal Reserve will need to step up its policy communications on the increase in inflation being only transitory and convince households, companies, and financial markets that there will be a return to lower rates of monthly inflation soon. In that it will be helped if the current supply-chain disruption and global energy price rises end.

The timing of halting quantitative easing and then reversing it, then increasing policy interest rates is yet to be clarified. For instance, an unanticipated policy reversal to guard against the loss of central bank credibility might result in a sudden financial market downturn and public sector balance sheet mismatches. How central banks respond to higher inflation will drive bond prices, with a combination of ending quantitative easing and higher policy rates.

The Federal Reserve also needs to prepare contingency plans for its actions if a 5 per cent inflation rate looks like becoming embedded, with inflation expectations rising. If, as we expect, it raises its inflation projections again following its December meeting, it may need such contingency plans sooner rather than later. Our view is that given the uncertainties about the duration of the higher inflation, wages and an employment rate still below pre-pandemic level, the Federal Reserve will be cautious in tightening policy, particularly as it will face a trade-off between stabilizing below-target employment or above-target inflation. Moving too far, too fast, could squander the best chance it will have to escape the trap of near-deflation and interest rates at the lower bound. If the cost of that is a period of moderately above-target inflation, they are likely to pay it.

Reference:

Dixon, H. (2021), ‘The simple arithmetic of inflation. Using “drop-in” and “drop-out” for exploring future short-run inflation scenarios’, National Institute UK Economic Outlook (Box A), Summer, pp 23-24.

Sanchez Juanino, P., Macchiarelli, C. and B. Naisbitt (2021), US inflation – peaking soon?, National Institute of Economic and Social Research (Box A), Global Economic Outlook, Series B., No. 4, Autumn, pp. 24-30.

NIESR (2021), ‘Global Economic Outlook’, Series B., No. 4, Autumn.