The implications of the Trade Union Bill

The government has today announced plans to place further restrictions on ballots for industrial action. This blog looks at the prevalence of industrial action in Britain and the likely implications of the Bill for employment relations.

How common are strikes in Britain today?

The government has today announced plans to place further restrictions on ballots for industrial action. This blog looks at the prevalence of industrial action in Britain and the likely implications of the Bill for employment relations.

How common are strikes in Britain today?

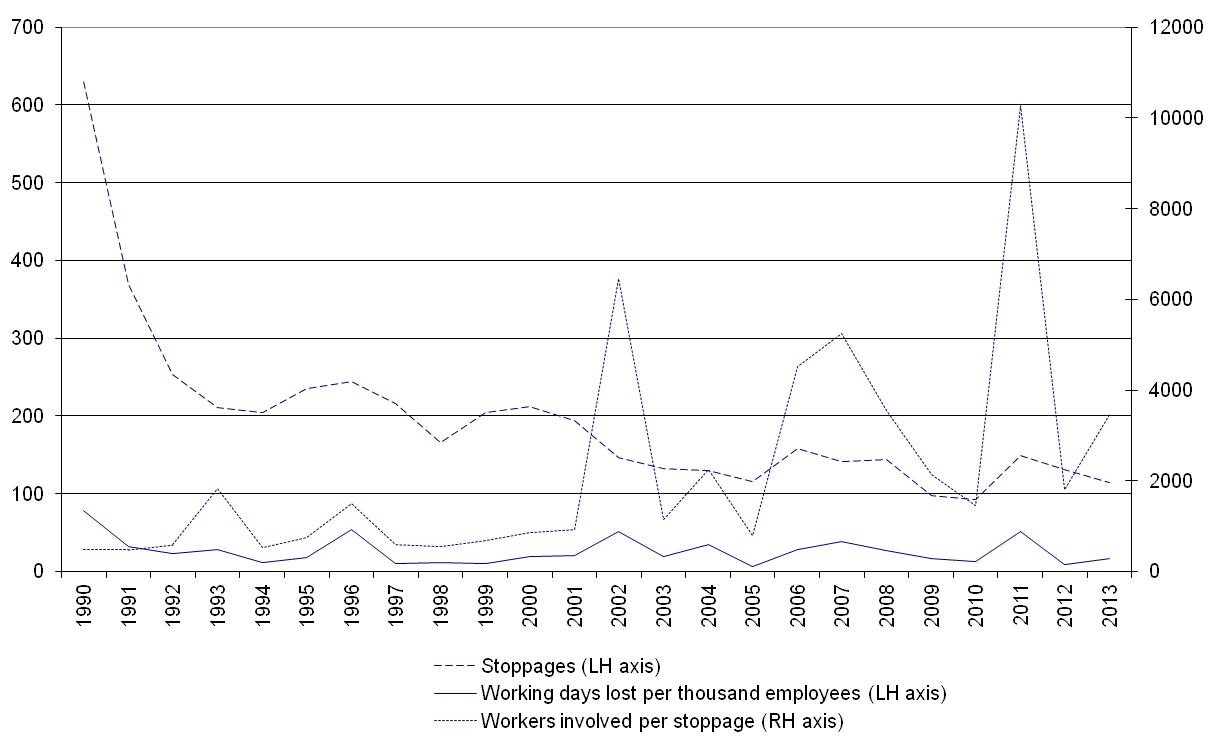

The late 1980s and 1990s saw a dramatic fall in the prevalence of industrial action and the numbers of working days lost. The number of days lost averaged around 300 for every 1,000 employees in employment during the 1980s, but has stood below 100 per thousand employees in every year since 1989, and has been below 50 per thousand for all but four of those years. The UK is thus, overall, now experiencing a prolonged period of relative industrial peace.

Figure 1: Working days lost to stoppages, 1989-2013

Source: Office for National Statistics

But what is particular about recent years is the dominance of the public sector in these statistics. The recent spikes in the series can mostly be attributed to short, large-scale strikes by public sector employees – for example those called in 2011-2012 in response to changes in pensions and ongoing pay freezes. In fact, the public sector now accounts for around four-fifths of all working days lost, despite accounting for only one fifth of all employment. This can be attributed to the enduring levels of union organisation among public sector workers (union membership density is around 55 per cent, compared with around 15 per cent in the private sector), the often-fractious relationships between unions and the government as employer, and the large-scale and networked nature of many public services. The final point is particularly notable, as there are few groups of private sector employees which have anything like the equivalent scope for large-scale disruption.

How does Britain compare with other EU countries?

Comparisons with other countries are fraught with difficulty, due to variations in practice between national statistical offices. However, the best readily-available estimates suggest that the UK has a lower incidence of industrial action than many other EU nations. An average of 24 days were lost per 1,000 employees in the UK over the period 2005-2009, which compares favourably with the EU average of 31 days per 1,000 employees, and is around half the rate of 45 days seen among the EU15.[1] Over this period, only six of the EU15 member states experienced lower rates than the UK: Austria, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden. In contrast, the rate in France was around five times higher than that seen in the UK – something largely due to the particularly high incidence of strikes among public sector workers in France.

How common are industrial action ballots?

To answer this question we can turn to data from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey (WERS), which has been co-sponsored by NIESR. In 2011 (the latest year that the survey was conducted), ballots were undertaken in just 1 per cent of private sector workplaces, but in 51 per cent of workplaces in the public sector. This latter figure partly reflects the particular dispute that was going on at that time (see above), but comparison with the previous survey in 2004 reiterates the point that the main effect of the Bill will be seen in the public sector.

Table 1: Industrial action by sector of ownership, 2004 and 2011

Percentage of workplaces

|

|

All workplaces |

Private sector |

Public sector |

|||

|

|

2004 |

2011 |

2004 |

2011 |

2004 |

2011 |

|

Any ballot |

3 |

7 |

1 |

1 |

19 |

51 |

|

Any industrial action |

2 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

32 |

|

Strike action |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

29 |

|

Non-strike action |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

Source: Workplace Employment Relations Survey

Base: all workplaces with 5 or more employees

What are the likely implications of the Trade Union Bill?

If passed, the Bill would require any successful ballot for industrial action to have a turnout of at least 50 per cent, and for ballots covering workers involved in certain public services (health, education, fire and transport) to have at least 40 per cent of eligible voters deciding in favour. It is not very clear how many ballots would fall foul of these thresholds, as there is no comprehensive data available on turnout or voting patterns. The Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) for the 40 per cent threshold is based on a sample of 78 ballots reported in the press and estimates a reduction of 65% in working days lost in transport, education, healthcare and the Border Force if both thresholds were enforced. So it seems clear that some unions will have to give greater attention to participation rates and so, in general terms, the Bill will inevitably make industrial action more difficult and expensive to organise. One key reason is that anyone abstaining from the vote – for example because they are genuinely undecided as to the right course of action – will effectively be counted as voting ‘no’. So any ballot which returns 50.1% of votes in favour will require 80% of eligible voters to turn out (or vice versa). This does not leave substantial margins for error on the part of the union.

There may be unintended consequences however. When the rules requiring formal ballots for industrial action were first introduced in the 1980s, some union negotiators found that, if they could adhere to the new rules, their negotiating position was actually strengthened (see here). Similarly, if unions can attain the thresholds proposed in the new Bill, they may find that their negotiating position is stronger than it would be in the current environment when many public sector strikes are portrayed by public sector employers as unnecessary and unfair on the general public.

A broader point, though, relates to the conduct of employment relations in the public sector. Robust negotiations can be expected to be a feature of a sector which has seen a prolonged squeeze on pay and job security (see an earlier blog for more on that). Restricting employees’ ability to strike may help public sector employers to maintain that squeeze, to the benefit of the public finances. In the short term, it may also benefit the customers of those services, who can better rely on transport, education and health services to be available when needed: preventing these ‘negative externalities’ from strike action is a key component of the economic rationale for the Bill as presented in the RIA. But if the content of the Bill makes public sector workers feel less able to shape their terms and conditions in a way that they view as fair, one might fear for the longer-term consequences on levels of motivation and morale that already seem to have been severely dented. That is one negative externality that is not considered in the RIA.

Update 14th September 2015:

To coincide with the 2015 TUC Congress, we have just published an assessment of trade union membership and influence in Britain, covering the period 1999-2014. The briefing note uses data from the Certification Officer, Labour Force Survey and other national surveys to chart trends in union membership density, organisational capacity and influence in the workplace.

[1] Author’s calculations from Carley (2010) after excluding Norway.