The long term economic impacts of reducing migration

Is immigration an answer to the challenges of the ageing population in developed countries? Or, over the long term, do the burdens immigrants place on the welfare state and public services – not to mention the impact of labour market competition on native wages and employment levels – more than outweigh the positive effects on growth and the public finances?

Is immigration an answer to the challenges of the ageing population in developed countries? Or, over the long term, do the burdens immigrants place on the welfare state and public services – not to mention the impact of labour market competition on native wages and employment levels – more than outweigh the positive effects on growth and the public finances?

In a paper we released today “The Long Term Economic Impacts of Reducing Migration: the Case of the UK Migration Policy” – Lisenkova et al., 2013, my colleagues from National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), University of Ottawa and I provide a quantitative assessment of the long-term impact of migration on the economy that may cast new light on this debate. As an experiment, we chose the migration target set by the senior partner of the current UK coalition government (the Conservative Party) to reduce the level of net migration from “hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands”. Our estimates show that the long term impact of this policy will be to significantly reduce GDP per capita and worsen the public finances. While gross wages increase slightly, the resulting increase in taxes means after-tax wages also fall.

UK net migration levels

The recent large influx of immigrants after the accession of the Eastern European countries to the EU in 2004 (so-called A8 countries[1]) brought migration policy to the forefront of the public agenda and political debate. Large net migration flows are a relatively recent phenomenon in the UK; until the 1980s emigration outweighed immigration. Tightening of the migration rules for non-EU migrants, introduced by the current government, combined with the economic downturn, has resulted in a fall from recent peaks; according to the most recent estimates during 2012 net migration was 177,000 – the lowest level since 2008, although still well above the “tens of thousands” target.

The principal net migration assumption in the 2010-based ONS population projections is that it will remain at 200,000 per year over the next 50 years[2]. Thus, if the UK government succeeds in achieving the “tens of thousands” target, then net migration has to be reduced by more than half relative to the ONS assumption. The goal of our paper is to model and analyse the overall economic impact of this policy.

General equilibrium model with detailed treatment of migrants

The analysis is carried out in a dynamic overlapping generations computable general equilibrium model (OLG-CGE) developed at NIESR: National Institute General Equilibrium Model of Ageing (NiAGE). This approach is widely acknowledged as the best tool for the modelling of issues associated with demographic change. Among the advantages of an OLG-CGE framework is its age-disaggregated nature, which makes it possible to study age-specific behaviour and the impact of changes in the population age structure on the economy. This dynamic approach contrasts with previous static modelling of the fiscal impacts of migration, such as that recently undertaken by Dustmann and Frattini (2013) and discussed on VOX.

In our model there are two types of individuals: foreign-born and native-born. We attempt to differentiate the native-born and foreign-born population as much as possible. The two groups exhibit different employment and wage rates, different levels of educational qualifications, as well as different probabilities of receiving welfare benefits from the government. All these are estimated from the Labour Force Survey. Moreover, because migrants age structure differs considerably from that of natives, so does their consumption of public services. Such detailed differentiation allows us to capture the multidimensional effects of migration on the labour market, aggregate demand and public finances. In this, we differ from the only previous attempt to model the long-term impact of migration on the economy and public finances undertaken by OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2013) – although interestingly our results are not dissimilar qualitatively or quantitatively. We compare two scenarios: the baseline scenario, which is built in line with the 2010-based principal ONS population projection, and a low migration scenario, which assumes the reduction of foreign net migration rates required to reduce overall net migration level by about 50%.

Significant reduction in net migration will have strong negative effects on the economy

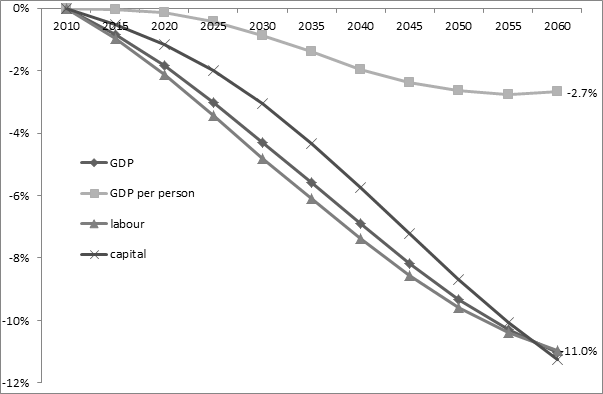

Our results show that a significant reduction in net migration has strong negative effects on the economy. First, by 2060 in the low migration scenario aggregate GDP decreases by 11% and GDP per person by 2.7% compared to the baseline scenario (see Figure 1). Second, this policy has a significant negative impact on public finances, owing to the shift in the demographic structure after the shock. The total level of government spending expressed as a share of GDP increases by 1.4 percentage points by 2060. This effect requires an increase in the effective labour income tax rate for the government to balance its budget in every period. By 2060 the required increase is 2.2 percentage points. Third, the effect of the higher labour income tax rate is felt at the household level, with average households’ net income declining because of the higher income tax despite the initial increase in gross wages due to lower labour supply. By 2060 net wage is 3.3% lower in the low migration scenario.

Figure 1. GDP and factors of production

Presented estimates are potentially the lower bound of the effects

As with any modelling exercise there are a number of caveats. From a purely technical point of view, our estimates arguably provide the lower bound of the potential effects. First, we chose the least strict interpretation of the migration target. “Tens of thousands” is not very precise but we decided that a level just below 100 thousand is sufficient to satisfy it. Second, the model does not take into account potential productivity spillovers from higher levels of immigration. Two potential positive productivity effects that have attracted attention recently are the potential effects on total factor productivity growth (e.g., Rolf et al, 2013) and the possible impact of imperfect substitution between natives and immigrants (Manacorda et al, 2013). Third, we are using a closed economy model for these simulations, which in the case of the low migration scenario results in a lower capital-labour ratio and lower returns on capital. If we used an open economy with perfect capital mobility, downward pressure on interest rates would lead to a capital outflow and even stronger negative effects of reduced migration. Fourth, while we take into account the direct impact of migration on population and hence public expenditure, including capital spending, we do not capture negative externalities resulting from congestion. Finally, of course, these simulations necessarily do not take into account the potential social impacts of higher immigration. This is a hotly debated area, which is beyond the scope of our study, but should be considered when formulating migration policy. Unfortunately, very often on this issue opinions trump evidence.

References

Dustmann, C. and Frattini, T. (2013), The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK, CReAM DP No. 22/13, Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration, London

Lisenkova, K., Mérette, M. and Sanchez-Martinez, M. (2013) The Long Term Economic Impacts of Reducing Migration: the Case of UK Migration Policy, NIESR DP No. 420, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, London

Manacorda, M., Manning, A. and Wadsworth, J. (2012) “The Impact of Immigration on the Structure of Wages: Theory and Evidence from Britain”, Journal of the European Economic Association, vol. 10, no.1, pp. 120-151

Office for Budget Responsibility (2013) Fiscal sustainability report, Office for Budget Responsibility, London

Rolfe, H., Rienzo, C. and Portes, J. (2013) Migration and productivity: employers’ practices, public attitudes and statistical evidence, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, London

[1] The A8 countries are the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

[2] 2010-based population projections were selected because they are the last vintage of projections available before the change in migration policy. In the latest 2012-based projections ONS took into account change in policy and adjusted principal long-term migration assumption from 200,000 to 160,000 per year.