Migrant pupils lead the way in promoting foreign languages in schools

A few weeks ago the BBC reported that young people are turning down the opportunity to study for a foreign language GCSE: its own analysis found drops of between 30% and 50% since 2013 in the numbers taking GCSE language courses in some areas of England. Employers voiced their concern that the future labour force will be ill-equipped for a post-Brexit Britain, and to forge trade deals across the world.

A few weeks ago the BBC reported that young people are turning down the opportunity to study for a foreign language GCSE: its own analysis found drops of between 30% and 50% since 2013 in the numbers taking GCSE language courses in some areas of England. Employers voiced their concern that the future labour force will be ill-equipped for a post-Brexit Britain, and to forge trade deals across the world.

But coverage of this trend revealed a blind spot. The UK doesn’t lack foreign language skills among its young people. It has a valuable supply of language skills in the 16.6 % of secondary school pupils and 21.2 % at primary level who come from homes where a language in addition to English is spoken. As the chart below shows, this figure has risen steadily over the last ten years.

Many of these children will have been born in the UK and not all will speak their heritage language fluently. However, new research we publish today, funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, finds pupils with other mother tongues value these and schools often do too, yet this valuable asset is so often neglected and unsung.

Learning English is the priority for migrant pupils starting school in the UK

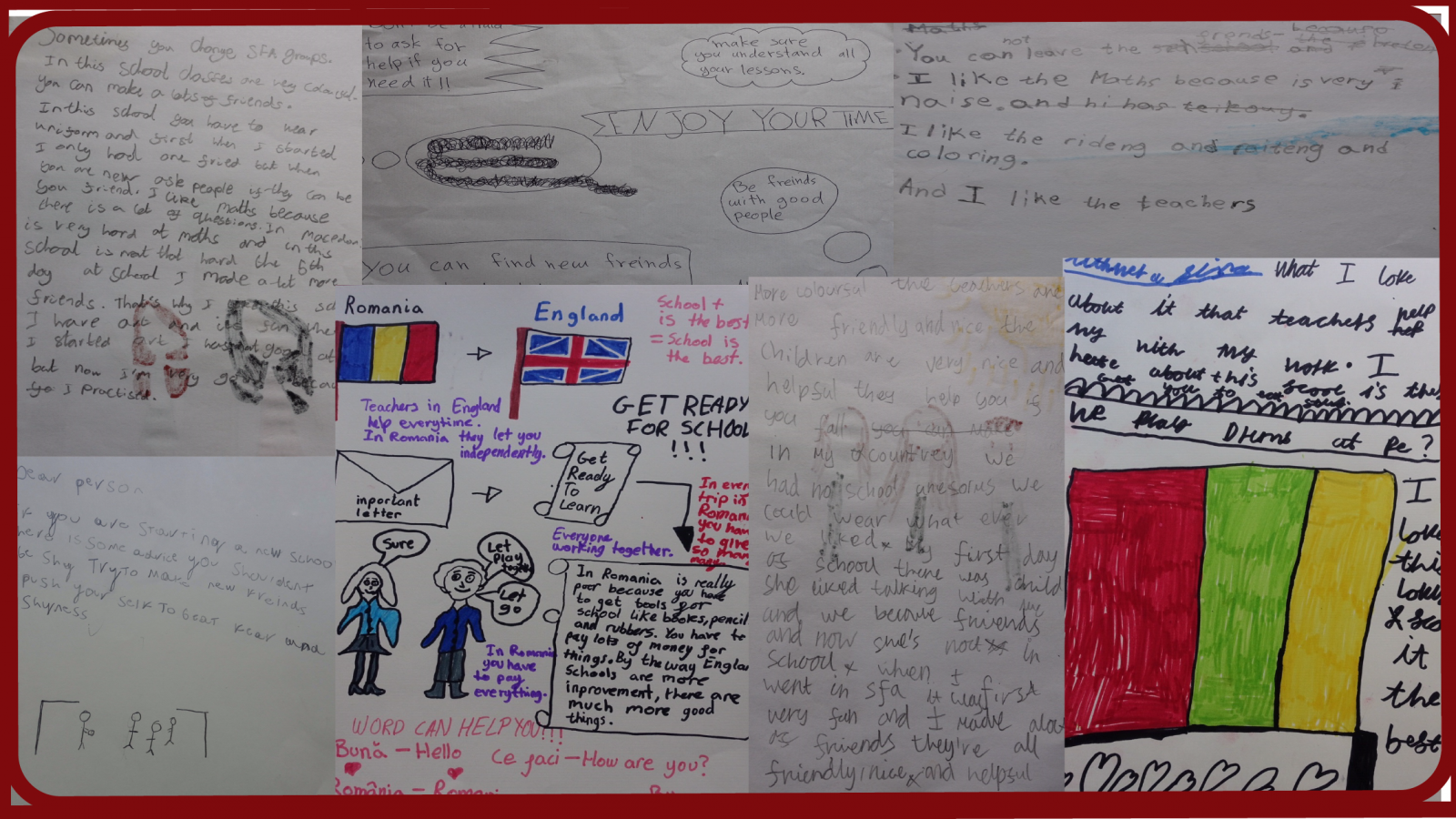

Pupils’ recollections of their first days at their new school were often strong since for many the experience had been a somewhat difficult one. Many said they had felt nervous and scared because they found the UK school environment strange, they lacked friends, couldn’t understand what was being said and what was expected of them inside and outside of the classroom.

Pupils recognised that in order to make friends and to achieve academically, they needed to become proficient in English. Many had seen this as challenging, including those who already spoke two languages. They strongly valued the support they were given to enable this to happen through additional support inside and outside the classroom. This was not always as good as schools would have liked because of funding cuts. But they found most migrant pupils progress quickly. This reflects national data analysed by SchoolDash which finds that, once disadvantage is taken into account, pupils in primary schools with high proportions of migrant pupils do better than average.

Migrant pupils value opportunities to speak and learn their mother tongue

Some newly arrived pupils found themselves in schools with teachers or pupils who could speak their mother tongue. Teachers also enjoyed the opportunity to keep up with their own conversational foreign language through exchanges in school corridors. For peer support, some schools trained pupils as ‘language ambassadors’ to help new arrivals across the school in explaining aspects of school life, effectively acting as translators and interpreters – valuable skills for their future careers.

A few schools had clubs which brought together pupils who share the same native language, in one case Arabic and these were led by teachers proficient in that language. Migrant pupils also valued the opportunity to read books in their mother tongue. Secondary pupils placed particular value on retaining proficiency in their first language. A pupil in Year 10 described in emotional terms how she liked to read books in her native Russian language in the school library:

‘…a comforting thing to do. When you move countries you leave your home and your friends behind but your language is something you can keep hold of’.

Pupils who lacked such opportunities expressed worry that their first language had deteriorated since they had started school in Britain, even if they spoke it at home. They recognised that what they had was more than part of their background and culture, and that languages are a skill that they might want to use in their future lives. Partly in recognition of this, and partly to improve pupils’ GCSE scores, all the secondary schools in our study gave pupils the opportunity to study for GCSE in their mother tongue where they could provide support. This both helped pupils to strengthen their formal written and spoken language skills and gave them the recognition they deserve.

To offer these GCSEs, schools sometimes had to bring in specialist support, or team up with other schools. But they felt it was important to make such efforts. The result, as national data shows, is that in the midst of the gloomy headlines about foreign language learning, ‘migrant’ languages such as Polish, Portuguese and Arabic are actually on the increase, to the benefit of everyone.

So while we should worry that UK born pupils are turning down opportunities to gain valuable skills for post-Brexit Britain, we should also celebrate the skills and abilities of multi-lingual children and young people from migrant backgrounds. They are just, if not more, important to the UK’s future as those who choose to study French or German.