A weaker global outlook and chronic Brexit uncertainty mean that the MPC should now sit on its hands

At this week’s meeting, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is unlikely to adjust the monetary policy stance substantially. Our latest economic forecast published last week suggests that the MPC should wait until the middle of next year before lifting Bank Rate above its current level of 0.75 per cent. This is because even though a soft Brexit seems more likely now it is offset by a weaker outlook for global demand and chronic levels of uncertainty at home.

At this week’s meeting, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is unlikely to adjust the monetary policy stance substantially. Our latest economic forecast published last week suggests that the MPC should wait until the middle of next year before lifting Bank Rate above its current level of 0.75 per cent. This is because even though a soft Brexit seems more likely now it is offset by a weaker outlook for global demand and chronic levels of uncertainty at home.

At its previous meetings, the MPC was faced with a softening in global economic data and adjusted the tone of its communication accordingly. At NIESR, we have used text-mining to measure policymakers’ inclination whether to tighten or loosen policy (Hantzsche and Mellina, 2018). Our Index of the Monetary Stance illustrates that the MPC has been signalling a more accommodative stance since December compared to the second half of 2018 (figure 1).

Our May forecast suspects that global economic growth will moderate in 2019 as a whole compared with previous years, but not plunge. We expect world GDP to expand by 3.4 per cent this year, compared to 3.7 per cent in 2018, before picking up to 3.6 per cent in 2020. This reflects slower growth in China and the temporary weakness in the Euro Area.

In the UK, uncertainty about Brexit has turned from a time-limited phenomenon to a sustained process and risks becoming a structural feature of the economy. Since the MPC previously met, the Article 50 period has been extended until the end of October and it remains unclear when and in what form the UK will exit the European Union. While our main-case forecast assumes that the UK will enter a transition period until the end of 2020 and remain a member of both the EU’s single market and customs union thereafter, we expect high levels of uncertainty to continue weighing down on demand throughout 2019.

Our forecast has business investment contracting by around 1 per cent in 2019 as a whole and consumption growing by only 1.5 per cent compared to 1.7 per cent last year and 2.1 per cent in 2017. As the risk of a no-deal Brexit recedes in our forecast, stocks built up at the end of 2018 and beginning of 2019 are run down, further acting as a drag on economic activity later in the year. GDP growth is forecast to reach 1.4 per cent in 2019 as a whole under the assumption of a soft Brexit, only 0.2 percentage points above the Bank of England’s February forecast which averages over different possible Brexit outcomes including a hard Brexit. In addition, inflation is forecast to remain around the Bank’s target of 2 per cent. Domestic cost pressures are robust but stabilising, with unit labour costs expected to grow at around 3 per cent in 2019, and are counteracted by slowing import price inflation.

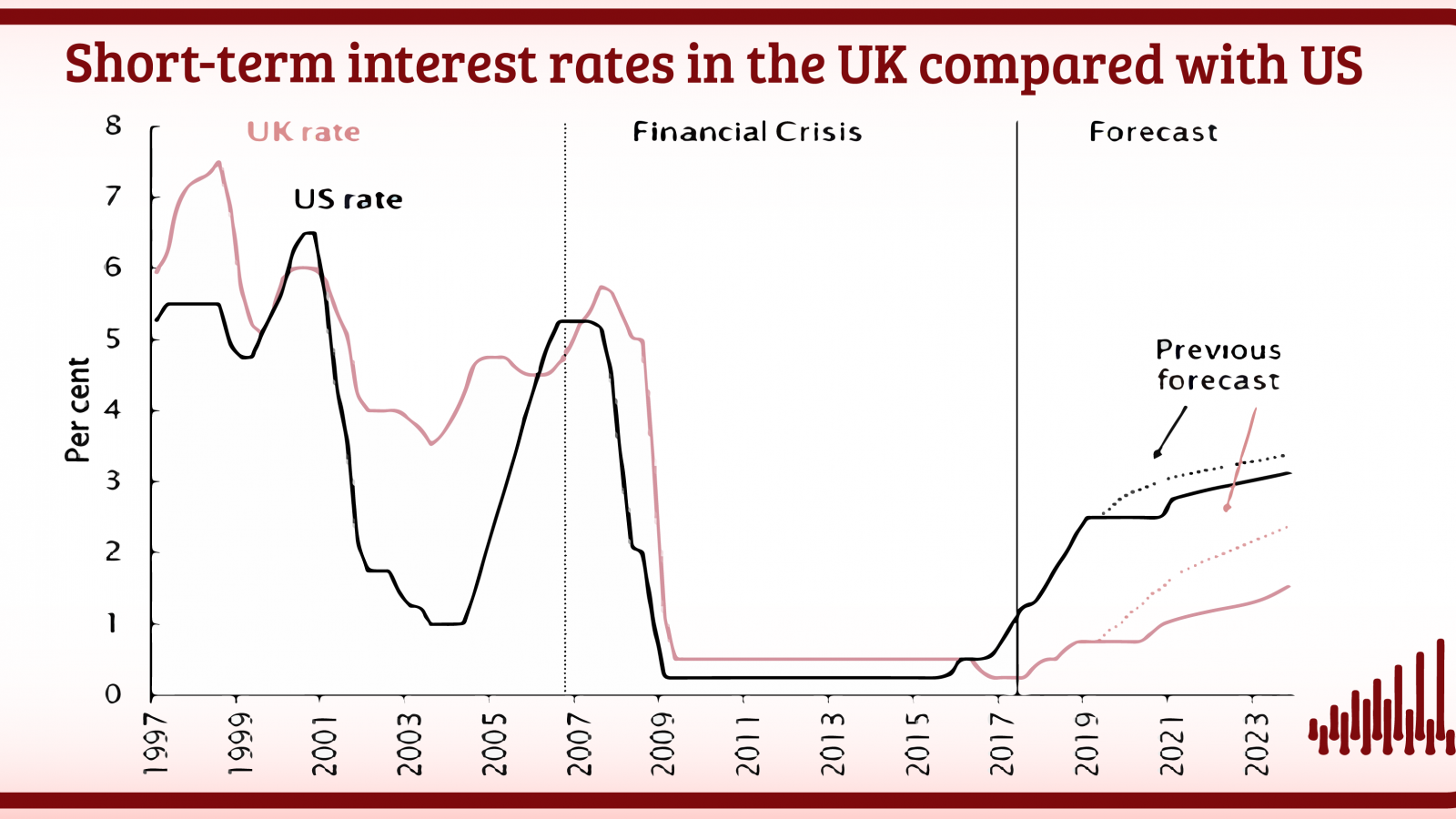

The weaker global outlook, Brexit-related uncertainty and stable inflation suggest that Bank Rate should remain at 0.75 per cent until the middle of 2020 and rise thereafter at a gradual pace. This implies a more accommodative stance than in our previous forecast published in February (figure 2), similar to that in other countries such as the US. It also implies that Bank Rate would not reach 1.5 per cent before the end of 2022, delaying the point at which the Bank would start to shrink its balance sheet in line with the guidance provided last June. By comparison, financial markets currently expect the next increase in Bank Rate to take place sometime in mid-2021, reflecting the pricing of risks associated with a more disruptive EU exit than that implied by our soft Brexit conditioning assumption.

The MPC has provided guidance on how the future path of Bank Rate is likely to be affected by different Brexit outcomes. It will balance the trade-off between the speed at which inflation is returned to target and the support that monetary policy provides to jobs and activity. In our February Review, we showed how monetary policy together with fiscal policy could be used to ease the adjustment to a harder Brexit. A no-deal exit, for instance, would require the MPC to see through a temporary flare-up in inflation by keeping Bank Rate steady as long as inflation expectations remain anchored. But what must be remembered in any scenario is that at best monetary policy can smooth the path to the long-run level of output, which is determined by the employment of factors of production and the level of their productivity. The destination is unchanged but the journey can be made less bumpy.