Taking Stock of Bernanke: The Original Sin of Forecasting

While the Bernanke review of forecasting at the Bank of England provides a welcome moment for us to assess the mistakes that have resulted from the current practices of the monetary policy committee (MPC), it should not be the final word. The original sin of economic forecasters is that they will always be wrong. Any honest producer of forecasts will make this point clear, as I have at every forecast release at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research since my appointment in May 2016.

Every consumer is therefore subject to caveat emptor, particularly if the forecast is the primary source of information for the deployment of bank rate. The MPC’s job is thus less to produce a perfect forecast, as one does not exist, but to articulate and manage the risks to price stability. A fundamental problem at the Bank of England is that the MPC is both producer and consumer of the forecast. And in my view, a fundamental guiding principle that should underpin reforms of the forecast process at the bank is that we must break that link decisively, as it sets up an unnecessarily defensive mindset, promotes groupthink and denies bank staff agency. Let us hand the production and ownership of the forecast to a better resourced and empowered bank staff, who work more closely with the macro community in the UK, and then allow the MPC to be careful consumers who may wish to stress risks and responses in accordance with their own analysis.

What exactly were the errors in monetary policy setting as we emerged from Covid? The bank failed to understand that monetary and fiscal policy were continuing to inject demand into the economy, even while it was recovering from Covid. The bank’s own forecast in early 2021 expected strong growth in domestic demand and yet this did not lead to a change in monetary conditions until December. Furthermore, that stance of monetary policy, with ultra-low policy rates and a continuing expansion in QE, amplified emergent inflationary pressures. These would also be further amplified by the crimped supply side, already suffering from Brexit and the resulting compression in trade and investment. Although the bank has finally decisively revised down its estimate of supply side potential, it remained worrying quiet on this question in the key 2021–22 period.

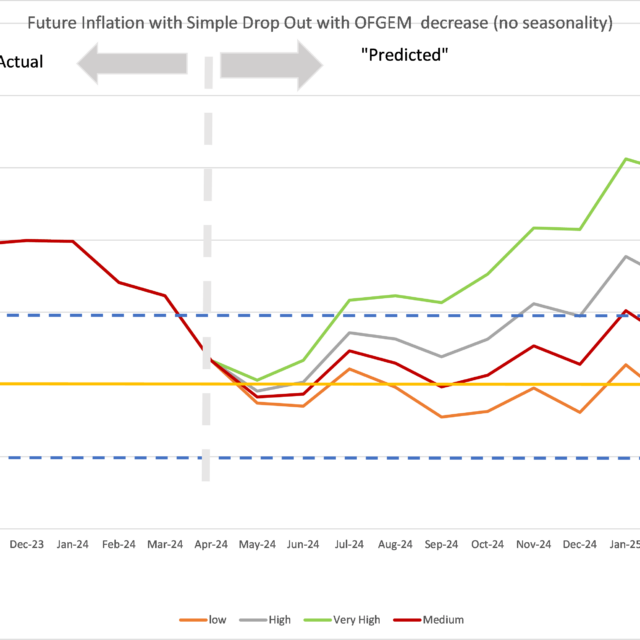

Given the gamut of uncertainties in modelling and understanding changing economic structure, it would be a mistake to try and push all risks such as these into some new monolithic model. Indeed, focusing on that reform would excuse the MPC from any responsibility for previous policy errors and judgements, as it could argue that it did not have the right tools. Basically, it did. It would be far better to have been clear about risks in its communication and to have deployed scenario analysis that would provide much more clarity on the path of bank rate. While scenarios look to be firmly on the agenda, the Bernanke review oddly stops short of asking for the publication of interest rate paths or Fed-style dot plots, which would provide much more clarity on the management of risks. And while it looks as though we may be about to scrap the fan charts, if used properly these can convey the balances and magnitude of risks that face policy-makers and can actually act to complement scenario analyses, which by and large will sit inside the fan charts. To me at least it is not a case of either or, as both can work side by side. There are two observations I would like to make that the bank and its watchers may wish to consider. During the interest rate normalisation cycle there were large and persistent errors in money market expectations of bank rate. This threw up two problems. It first suggested that the MPC were not communicating well the risks to price stability and the probable responses in bank rate. This started with the infamous misdirection of November 2021.

The second problem is that if the bank conditions its forecast on mistaken market expectations, the forecast will itself be biased. We have to think carefully through what interest rate conditioning assumption we use – the current practice of market rates and a constant interest rate assumption further guarantees a forecast that will be wrong. Bank staff could easily generate paths for bank rate from their own modelling of the economy that correspond to different preferences on inflation or output without prejudice to the final choice made by the MPC. To some extent we have seen some of that with speeches that showed what would have happened to employment and output had bank rate sought to bring inflation back down to target quickly. Such a practice would be a more useful benchmark for the MPC.

At the same time, we can also note that the path of bank rate followed very closely that of the US federal funds rate. While it might be case that the shocks and economic structures in the UK implied the same path as the Federal Reserve, it seems at face value unlikely. And this questions whether the MPC was willing to use its independence to the full extent, possibly feeling that it had to stay close to some notion of international norms and not stand out from the central bank crowd. It is tempting to ask what is the point of an independent central bank with its own floating currency if we are determined to shadow an external policy rate? Note that these two points are not especially model dependent; they are arguing for more explanation of bank thought and openness about dissent, which reflects genuine uncertainty about the likely future path of the economy and the courage to act. A model is at best a guide, but we still need to be wary of what direction it is sending us. The Bank of England has a history of commissioning reviews every few years and then committing to implementing the recommendations. But this time should be different. The near loss of price stability and monetary policy credibility has been a risk too far for the UK economy – the price level is now some 14% above the level we might have anticipated in the middle of 2021 had the inflation target been met consistently over this period. That is a huge deviation and has shocked households and firms. And so, this review should be the start of a more profound discussion about how the bank needs to reform its internal practices, encourage more internal and external debate, and interact more openly to respond to the failings we have observed. It should not be the end but a start.