The UK economy is marred by stagnant growth in productivity and output. This poor economic performance puts pressure on the public finances and reduces ‘fiscal headroom’ – the gap between the public finances and proposed spending plans.

This is further exacerbated by an increasing need for government spending. For example, money is urgently needed to improve health, social care and education services. Significant investments are also required in infrastructure, particularly outside London.

Further spending on training and skills development would help to boost productivity; and large financial commitments are required to achieve net-zero targets. In addition, policy-makers face pressures to increase defence spending in response to escalating geopolitical tensions. Tightening the purse strings would not be straightforward.

These challenges are coupled with a ratio of public debt to GDP that sits at a 60-year high and a tax burden that sits at a 70-year high. All of this should provide impetus for a critical evaluation of the UK’s approach to taxes and spending.

But the available headroom to tackle these challenges is constrained by two key factors: economic performance and the fiscal rules.

The UK’s current fiscal rules state that the debt-to-GDP ratio should be falling within a five-year horizon and the ratio of the annual budget deficit to GDP should be below 3% by the end of the same period.

These rules are intended to guide the government towards a sustainable fiscal position and act as a commitment device to engender confidence among international investors and financial markets.

While these rules have been a feature of UK policy since the 1990s, they have been far from static. They are set by the Chancellor of the Exchequer (as opposed to being bound by law) and, over the decades, they have been subject to a number of revisions and adjustments depending on the government’s fiscal strategy and the economic climate.

But the National Institute of Economic and Social Research’s (NIESR) Spring 2024 UK Economic Outlook indicates that current government spending plans do not meet the current fiscal mandate. This contrasts with the projections contained in the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) March 2024 Economic and Fiscal Outlook. The variation is driven primarily by differences in expected rates of economic growth.

This suggests that the current fiscal rules may not be fit for purpose. Of course, there must be a mechanism by which the public finances are made sustainable, but they must also meet the needs of the population.

Specifically, they should acknowledge the interrelated nature of economic performance and budgetary expenditures: the expected rate of economic growth is not completely independent of fiscal policy.

For example, the current rules can hamper economic growth by placing unhelpful constraints on public investment. Specifically, during economic downturns, these rules disproportionately favour reductions in investment expenditure as they demand improvements in the debt-to-GDP ratio within a short five-year timeframe. In the long run, this can hinder GDP growth and the future tax base, undermining the original rationale for keeping debt down.

In other words, this creates a de facto ‘pro-cyclicality’ for public investment – during periods of economic contraction, tax receipts typically fall, thereby further limiting fiscal headroom.

Fiscal rules and economic performance are therefore intimately linked and subsequently shape policy-makers’ fiscal choices. The efficacy of these rules, and how they can be enhanced to improve the state of the public finances, are of crucial importance, particularly in an election year.

Setting rules is vital for broadcasting a message of financial responsibility. But getting this wrong can risk policy-makers getting trapped in a net of their own making.

Forecasts and fiscal rules

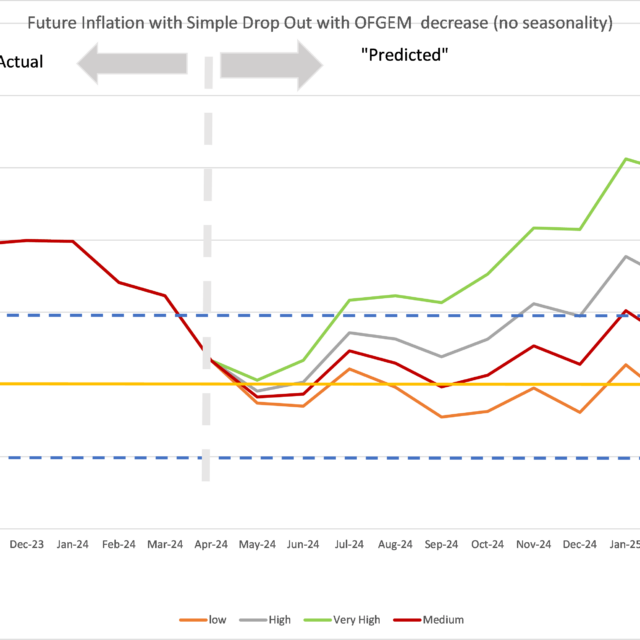

In contrast with the OBR projections, the NIESR Spring 2024 forecasts indicate that the current government is likely to miss its fiscal targets. Figure 1 shows the forecasts for the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Figure 1: Debt-to-GDP ratio and forecasts

Source: NIESR

The OBR forecast shows debt-to-GDP peaking in the second year of the forecast, at 98.8%, and then falling slightly during the forecast window (indicated by the shaded grey area). Meanwhile, the NIESR forecast shows debt-to-GDP rising to 101.5% in the final year of the five-year horizon; the ratio stabilises and then falls after the fifth year of the rolling horizon.

While the official fiscal target excludes public debt held by the Bank of England, a similar dynamic emerges if the projected values for public debt held by the Bank of England are subtracted from NIESR’s forecast.

This differential is driven primarily by the more optimistic growth path for GDP that the OBR expects. Given the immediate connection between growth and the projected debt-to-GDP ratio, the underlying assumptions of each model can make a vital difference to the overall predictions.

According to NIESR’s Spring 2024 forecast, the deficit-to-GDP ratio is also set to miss its 3% target by the end of the five-year horizon (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Deficit-to-GDP ratio forecasts

Source: NIESR

At the end of the forecast horizon, the OBR projects that the deficit-to-GDP ratio will be below the 3% target, at 1.2%, while NIESR projects this to be at 4.5%. The latter projection attributes the higher deficit to an insufficient increase in the tax base, exacerbated by the two reductions in national insurance contributions over the past six months.

But failure to meet the fiscal targets raises questions about the credibility of the existing fiscal framework and its effectiveness in guiding fiscal policy. The inability to adhere to these rules suggests the need for a more flexible approach to fiscal policy, which can respond to short-run economic fluctuations as well as allowing for credible increases in long-run public investment.

In the context of inflation coming back down to target, fiscal drag – that is, the increase in tax revenue that results from higher incomes not being matched by rises in tax allowances – can no longer be exploited as a means of raising revenues.

This means that it is highly likely that the winners of the 2024 general election will have to raise taxes if they wish simply to maintain the existing provision of government services.

All this provides further impetus for reforming the fiscal framework. The current rules do not only create arbitrary targets that preclude sound fiscal decisions, but they are also not being met in practice. This suggests it is time for change.

A revised framework

A revised fiscal framework appears essential. For example, a new framework could incorporate public sector net worth as a target. This provides a broader measure of public debt sustainability, inclusive of what the government owns and what it owes.

As domestic public sector net worth is relatively low by comparable international standards, the inclusion of this as a fiscal target could help to create sustained public investment and economic growth.

Another revision to the rules would be to discount public infrastructure investment from the deficit measure. This would mean that it would be separated out from current day-to-day spending.

Economists treat private consumption and investment differently with regard to taxes and regulations. This is because distortions to investment decisions accrue over time and affect long-run potential growth. So, it follows that a distinction should also be made between public consumption and public investment, as public investment also can have a positive impact on economic growth.

Further important aspects of fiscal framework reform include the timing and certainty of fiscal events. For example, the upcoming spending review was confirmed (in the Spring 2024 budget) to be completed after the general election. This is especially pertinent because if there were to be any delay to this spending review process, it would cause significant disruption.

Any reform of the fiscal rules should also aim to uncouple fiscal policy choices from political cycles. This could be done by establishing fixed dates for fiscal events, such as budgets and spending reviews.

Specifically, HM Treasury should be empowered to establish a fixed schedule for fiscal events so that their timing is insulated from political considerations, in the same way that meetings of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee are scheduled many months in advance.

This would help to generate continuity in announcements and go some way to insulating fiscal choices from political expediency. Otherwise, fiscal policy decisions remain disproportionately sensitive to short-run political objectives, which works to the detriment of long-term economic objectives.

Conclusion

Whoever wins the 2024 general election will face significant fiscal and economic challenges. Solving these requires a meaningful reform of the existing framework.

A revised approach that creates an incentive structure emphasising long-term economic stability, has the capacity to create an environment more conducive to robust economic growth.

While traditional measures of public debt, such as the debt-to-GDP ratio, should remain as important components of any revised fiscal rules, they ought to be considered alongside other targets, such as public sector net worth.

But the real long-term risk to the public finances arises not from missing the existing fiscal targets, but from an excessive singular focus on fixed debt-to-GDP and deficit-to-GDP targets at the expense of sound public investment to raise productivity and long-run output.

On a wider level, boosting productivity growth will ultimately improve the state of the public finances and enable greater fiscal headroom, helping policy-makers to meet the growing demand for the provision of vital government services. Rules are there for a reason: getting them right is crucial.