Can US Policy Choices Explain Economic Divergence?

The divergence in economic performance among advanced economies since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic has become increasingly evident, with the US notably outperforming its peers. As of the end of the first quarter of this year, the cumulative growth rates in the US since the start of the pandemic have reached 9%. For comparison, this figure is 3.6% in Japan, 3.3% in the Euro Area, and only 1.5% in the UK (figure 1).

1. US real GDP relative to G7

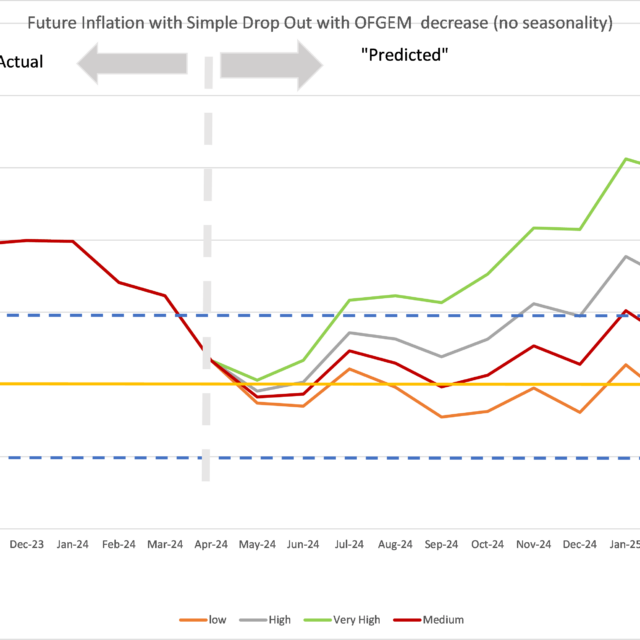

Even more impressively, this relatively strong economic performance has not been accompanied by higher inflation. As shown in figure 2 below, the cumulative inflation rate in the US, at 17.4%, is lower than that of both the UK (20.4%) and the Euro Area (18.5%) since the start of the pandemic.

2. US price levels relative to G7

In addition to being relatively less affected by the negative consequences of the Russia-Ukraine war and subsequent surge in oil and gas prices, the extraordinarily high degree of fiscal stimulus may be playing the most important role in this relatively strong growth performance in the US. In fact, a simple decomposition of US GDP growth already shows that more than 80% of growth in 2023 comes from either direct government spending (investment and consumption) or private consumption, which was largely as a result of indirect fiscal supports, including cash transfers (figure 3). We should also note the importance of excess savings and pent-up demand during the pandemic. While it is hard to disentangle these factors, we can reasonably argue that similar dynamics were at play in other G7 countries. Therefore, we can argue that the relatively strong performance of the US economy may, to some extent, be temporary.

3. Decomposition of US GDP growth

The natural follow-up question is what would be the price of such a large degree of fiscal expansion and what would happen to the US economy when (rather than if) fiscal policy is normalised? Though it is hard to tell, our recent analysis on the macroeconomic impact of a possible US fiscal consolidation can give some hints. The US Bureau of the Fiscal Service estimates that to keep the public debt sustainable, the US government should increase the primary surplus-to-GDP ratio by 4.5 percentage points each year from 2024. Our analysis, assuming a combination of tax increases and spending cuts, shows that such a fiscal consolidation reduces US GDP by around 2–3% by 2040. What does this all mean for monetary policy? First, although policy interest rates were increased to decade-high levels, the overall economic policy setting has not been so restrictive in the US, given the degree of the fiscal expansion. In fact, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s National Financial Conditions Index shows that overall financial conditions are still loose, especially compared with the tightening implemented in the late 1970s and early 1980s. We live in a completely different – much more financialised – world now compared with the early 1980s, but this is something that should be discussed more. Second, it is hard to tell if the US monetary tightening has not negatively affected economic activity in the US given GDP growth has been mainly driven by fiscal stimulus. Finally, it would be a mistake to think that monetary policy has no more role to play in fighting US inflation. We should keep in mind that it is also central banks’ responsibility to anchor inflation expectations, which I believe largely drives the stickier part of the US inflation. Considering the geopolitical risks, especially arising from the Middle East, any early action to lower interest rates may harm the disinflationary process by affecting inflation expectations.