Inflation, the Fed and Economic Long Covid

The Federal Reserve underpredicted 2021’s US inflation pick-up but believes the current inflation spike is temporary. If this assessment proves wrong, the result could be lasting higher than targeted inflation, an extended period of high unemployment, or both. To avoid this economic long Covid, the Fed should taper soon to give itself the flexibility to respond with higher rates if inflation fails to retreat as much as it expects.

The Federal Reserve underpredicted 2021’s US inflation pick-up but believes the current inflation spike is temporary. If this assessment proves wrong, the result could be lasting higher than targeted inflation, an extended period of high unemployment, or both. To avoid this economic long Covid, the Fed should taper soon to give itself the flexibility to respond with higher rates if inflation fails to retreat as much as it expects.

Fed Targets may Conflict

The Fed’s goal is 2 percent inflation in the price deflator of consumers’ expenditure (PCE). It has given itself more flexibility since last year, aiming to average 2 percent inflation, allowing future overshoots to compensate for past shortfalls. It is vague about the averaging period and the extent and duration of any excess. Given the current higher inflation uncertainty, this ambiguity risks higher inflation expectations (Apergis and Apergis, 2020). If inflation expectations are adaptive, high inflation in the coming months could leave the Fed with a far from transitory problem.

Alongside 2 percent inflation, the Fed aims to achieve “maximum employment” and “moderate long-term interest rates.” Maximum employment is undefined quantitatively but includes reducing the unemployment rate, raising the participation rate, and ensuring a broad and inclusive jobs recovery. The Fed seeks to reverse the 3.8 million rise in unemployment and 6.7 million jobs fall between early 2020 and June 2021, with millions of workers exiting the labour market altogether.

Labour participation rates to rise?

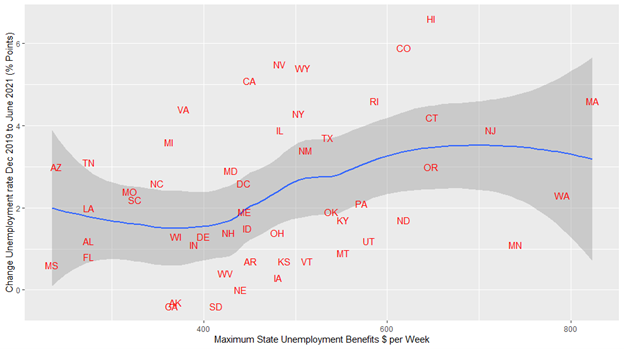

Wages are central to inflation’s evolution, but doubts about labour participation rates obscure the prospects. Firms frequently report recruitment problems and paying higher wages. Labour market compositional shifts due to the pandemic obscure the picture — poorly-paid workers were more likely to be laid off last year and rehired this year, distorting the average earnings figures. Future labour force participation is uncertain: pandemic concerns may be keeping some workers away; some may have childcare issues or took retirement. Chart 1 suggests more significant increases in unemployment since end-2019 in states with higher unemployment benefits, so labour market participation may increase after enhanced unemployment benefits of $300 per week cease in remaining states in September.

Unemployment, Fed policy choices and inflation

Chart 2 shows that the post-2000 unemployment/core inflation relationship is weak, suggesting that the Fed can reduce unemployment to 4 percent or below while achieving inflation close to the target. However, the Fed exploiting the weak unemployment/inflation relationship could shift the curve up, with economic agents perceiving a more inflation-tolerant Fed prioritising labor market goals.

The Path to rate Hikes Will be Long

The Fed faces timing constraints in adjusting monetary policy. In the last rate cycle, it phased out QE over ten months before raising rates; it might take a year this time. Unless tapering starts immediately, therefore, the inaugural rate hike looks unlikely before 2023. While premature tightening could impede meeting labour market objectives, the risk of waiting is an inability to raise rates soon enough if underlying inflation keeps rising.

Inflation expectations hold the key

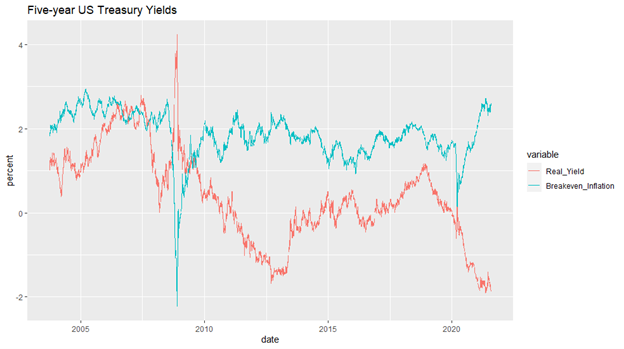

Inflation expectations are crucial. Since the end of 2019, market pricing and household surveys suggest 5-year inflation expectations rose by about three-quarters of a percentage point (Charts 3 and 4). The University of Michigan’s survey of consumers suggests expected inflation of 4.8 percent over the next year and 2.9 percent over the next five years. Chart 3 suggests that higher expected inflation combined with QE is distorting real yields downward. Thus, ending QE risks a substantial upward yield shift, perhaps larger than 2013’s “taper tantrum” because inflation and growth are higher now and real yields are lower. Fed moves will need to be measured and transparently flagged in advance to reduce sell-off risks.

Risks of a Persistent Inflation Overshoot Have Risen

Higher inflation expectations are welcome after core PCE’s 10-year average of 1.7 percent. However, expectations already suggest a persistent modest overshoot of 2 percent despite aggregate spare capacity. If inflation expectations ratchet up further, Chart 2’s unemployment/inflation relationship a high unemployment cost of re-lowering inflation. Thus if the Fed is mistaken about the extent to which the inflation surge is temporary, either higher inflation or high unemployment, or both (stagflation), will turn out to be an unpleasant economic form of long Covid.

Chart 1 Source FRED, BLS, State Websites, Saving to Invest.

Chart 2 is core PCE and unemployment.Sources: FRED, BLS

Chart 4 is 5-year Michigan inflation expectations % year and 1 year Source: Quandl and University of Michigan.

References

Altonji, J., Contractor, Z., Finamor, L., Haygood, R., Lindenlaub, I., Meghir, C., O’Dea, C., Scott, D., Wang, L., & Washington, E. (2020). Employment effects of unemployment insurance generosity during the pandemic. Yale University Manuscript.

Apergis, E., & Apergis, N. (2020). Inflation expectations, volatility and Covid-19: Evidence from the US inflation swap rates. Applied Economics Letters, 1–5.

Armantier, O., Koşar, G., Pomerantz, R., Skandalis, D., Smith, K., Topa, G., & Van der Klaauw, W. (2021). How economic crises affect inflation beliefs: Evidence from the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 189, 443–469.

Cavallo, A. (2020). Inflation with Covid Consumption Baskets (Working Paper No. 27352; Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27352

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. (n.d.-a). Inflation Sensitivity to COVID-19. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Retrieved July 25, 2021, from https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/indicators-data/inflation-sensitivity-to-covid-19/

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. (n.d.-b). Monitoring the Inflationary Effects of COVID-19. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Retrieved July 25, 2021, from https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2020/august/monitoring-inflationary-effects-of-covid-19/

FileUnemployment.org. (n.d.). Unemployment Benefits Comparison by State—FileUnemployment.org. Retrieved August 1, 2021, from https://fileunemployment.org/unemployment-benefits-comparison-by-state/

Ganong, P., Noel, P., & Vavra, J. (2020). US unemployment insurance replacement rates during the pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104273.

Guo, J., Williams, N., Alalwani, A., Jiang, Z., Pang, J., Smutny, S., & Zeng, L. (2021). The Impact of Increased Unemployment Benefits During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Haubrich, J. G., & Millington, S. (2014). PCE and CPI Inflation: What’s the Difference? Economic Trends. https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-trends/2014-economic-trends/et-20140417-pce-and-cpi-inflation-whats-the-difference

Petrosky-Nadeau, N., & Valletta, R. G. (2021). UI Generosity and Job Acceptance: Effects of the 2020 CARES Act (No. 2021–13). Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2021/13/

Reimann, N. (2021, May 7). U.S. Chamber Of Commerce Wants End To $300-A-Week Federal Unemployment Benefits—Blames It On Bad Jobs Report. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nicholasreimann/2021/05/07/us-chamber-of-commerce-wants-end-to-300-a-week-federal-unemployment-benefits-blames-it-on-bad-jobs-report/

Reinsdorf, M. (2020). COVID-19 and the CPI: Is inflation underestimated? IMF Wrrking Papers, 2020/224.

Saving to Invest. (2014, November 11). 2021 to 2022 Maximum Weekly Unemployment Benefits By State. $aving to Invest. https://savingtoinvest.com/maximum-weekly-unemployment-benefits-by-state/

Seiler, P. (2020). Weighting bias and inflation in the time of COVID-19: Evidence from Swiss transaction data. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 156(1), 1–11.

US Chamber of Commerce. (2021, May 7). US Chamber Calls for Ending $300 Weekly Supplemental Unemployment Benefits to Address Labor Shortages. US Chamber of Commerce. https://www.uschamber.com/press-release/us-chamber-calls-ending-300-weekly-supplemental-unemployment-benefits-address-labor

Will Unemployment Benefits Be Extended Again in 2021 or End Early in More States? Latest PUA, PEUC and Extra $300 Weekly Payment (FPUC) News and Extension Updates. (2020, May 14). $aving to Invest. https://savingtoinvest.com/will-extra-unemployment-benefits-be-extended-in-2020-and-2021/

.png)