Why is UK Productivity Low and How Can It Improve?

With improving UK growth, so it reaches a trend rate of 2.5%, a central pillar of the new Conservative government’s economic policy, Professor Stephen Millard speaks to Dr Issam Samiri to discover some of the historic reasons behind the UK’s sluggish productivity. Are the measures announced during the ‘mini-budget’ sufficient to address some of the systemic challenges?

The government have argued that it is time for a new ‘Growth Plan’. How bad has UK productivity growth been since the financial crisis, both relative to the past and to other developed economies?

It is important to start by reminding ourselves what we generally mean by productivity and why it matters. By productivity, most economists and economic commentators refer to labour productivity. This notion reflects how much economic value is generated at the national level by the amount of work supplied by the country’s workforce. A standard measure of (labour) productivity is output per hours worked, which can be obtained by dividing the volume of goods and services produced by the country in a year (real GDP) by the number of work hours supplied by the country’s workforce during the same year. Productivity can be loosely described as a measure of how smart we work instead of how hard we work. For instance, a country can work very hard by increasing the aggregate number of hours worked in a year while generating little extra value. This is the type of low-productivity economy we want to avoid if we care about the population’s living standards. The evidence in this regard is clear. The UK’s real wages improved with the country’s productivity before 2008 and stagnated as productivity grew at a much slower pace in the post-2008 period.

The United Kingdom’s economy has been plagued by anaemic productivity growth since the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Between 1974 and 2008, the UK’s productivity grew at an average rate of 2.3% a year, a much higher rate than the growth rate between 2008 and 2020 at around 0.5%. This is a substantial slowdown, unparalleled in the period of the country’s economic history for which we have decent measures of economic aggregates (from the mid-18th century onwards).

Productivity growth has been poor in most advanced economies since the global financial crisis (GFC). However, the UK’s economy has underperformed most comparable economies after 2008. To compare the UK’s productivity performance to the experiences in other countries, we need to adjust for inflation in each country and changes in the value of each country’s currency. Such an exercise allows us to easily contrast the 0.27% average growth rate of the UK’s productivity (in US dollars 2010 PPP per hours worked) between 2008 and 2019 to the much higher rates of 1% in the United States and 0.7% in France and Germany. While slower productivity growth since 2008 is not a UK-specific problem, it is a worse problem in the UK than in most comparable advanced economies.

What factors, in your opinion, have combined to lead to this poor productivity performance?

When studying national productivity performance, most economists start by examining the country’s capital levels. Higher levels of aggregate capital usually mean more output for the same number of hours worked and therefore, higher productivity. Unfortunately, the share of GDP dedicated to capital formation has been low in the UK compared to the US, France, and Germany in most years since the 1960s, and the gap has widened further since the early 1990s.

The UK economy suffers from chronic underinvestment in the public and business sectors. Public investment collapsed from a long-term average of 4.5% of GDP between 1949 and 1979 to around 1.5% after 1979. Similarly, the share of the UK’s GDP dedicated to business investment has been trending downwards since the early 1960s. There are structural reasons for these trends. For instance, capital goods’ prices decreased substantially relative to consumption goods over the last half-century. This means that a smaller share of GDP can buy the same quantities of capital goods now than 20 years ago—Think of how much a computer with a certain computing power costs now compared to 30 years ago. While investment goods are now much cheaper, the UK’s capital to output ratio did not change much since the 1960s, meaning that the UK used lower capital prices to spend less of its GDP on investment instead of improving the economy’s capital intensity as measured by the capital to GDP ratio. In addition, the UK economy’s industrial composition has changed, decreasing the share of the capital-intensive heavy industries.

Trends such as lower capital relative prices and rebalancing in favour of less capital-intensive industries are not unique to the UK. They are unlikely to justify the lower investment shares in the UK relative to similar economies on their own. Furthermore, the UK’s underinvestment puzzle is deepened by the downward trend of real interest rates. Even the recent tightening of monetary policy by the bank of England has not reversed this trend yet, as inflation is currently around 9.9%. Economists tend to think that low real interest rates spur investments by decreasing the financing costs businesses face when funding new capital. To a large extent, the issue of low investment shares in the UK is still an open question, and economists are still grappling with it. The uncertainty regarding trade terms for UK businesses after the country left the EU single market certainly contributed to curbing the short-lived rebound in business investments that preceded 2016. However, it is hard to blame Brexit for what is essentially a structural feature of the UK economy.

To what extent do you think the government’s tax-cutting ‘mini budget’ will help spur productivity growth?

Mainstream economics theory argues that all capital taxation negatively distorts economic outcomes. For example, lower corporate taxation means, in theory, more investment and, therefore, higher productivity. Moreover, many empirical studies indicate a positive relationship between lower corporate tax rates and higher corporate investments. The UK brought its corporate tax rate down through successive cuts, from 28% in 2010 to 19% in 2017. This meant that the UK corporate tax rate has been significantly lower than other G7 countries and the lowest in the G20 for many years. Has this been enough to spur investment and productivity? The short answer is no. This is because aggregate investment and productivity outcomes depend on several interconnected factors. For instance, businesses facing great uncertainty regarding the future are unlikely to respond to tax cuts by increasing investments. Moreover, not all investment is private; some of it is public and is unlikely to be replaced by private investments. Unfortunately, lower tax receipts do not bode well for all forms of public investments in the long run. Finally, lower tax rates are unlikely to spur direct foreign investments if international investors lose faith in how the government manages public finances. This is a crucial point given the bad performance of the British pound in the days leading to and since the announcement of the government ‘mini budget’. If the negative vote of confidence by markets is confirmed, the cost of public debt will increase further, worsening the country’s fiscal picture.

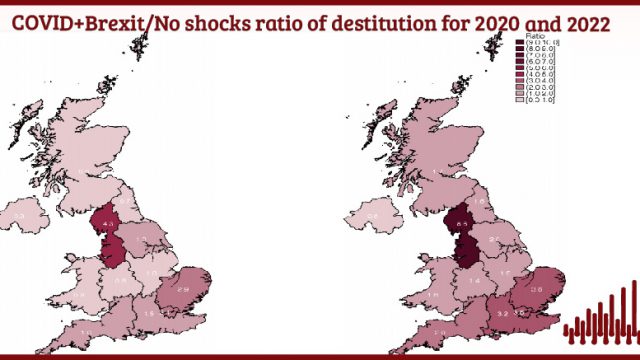

On the other hand, if economic growth materialises and continues for many years, it could help the prospects of the UK’s productivity by improving private investment. Moreover, sustained economic growth would also decrease the public debt to GDP ratio, thus reassuring markets and reducing borrowing costs while creating the fiscal space required for future governments to make the public investment in infrastructure and skills needed to foster productivity growth. Unfortunately, it is hard to predict the impact of many of the announced policies on long-term growth at this stage; we lack much of the implementation details, and more importantly, the outcomes of such policies are always uncertain. For example, the newly announced “investment zones” could foster productivity growth in the long run and help close the gaping regional productivity differences in the UK. But besides headlines regarding more tax cuts for businesses, much of the implementation detail remains unclear. The government is still to coordinate with local authorities before finalising plans. As a result, there is also a lot of uncertainty around what these “investment zones” will be in practice.

In any case, the government growth plan is designed for investment and growth to be led by the private sector. No market economy can achieve growth without a dynamic business sector. However, given the chronic underinvestment by UK businesses for over 50 years throughout different tax regimes, the success of such an approach remains a gamble.

What do you think the government should be doing?

A single government cannot fix the UK’s poor productivity performance. It requires long-term planning and a persistent approach lasting over multiple governmental mandates. Constant changes in the UK’s economic policy cannot help in improving the country’s productivity in the long run. This so-called ‘policy churn’ makes it impossible to carry out the structural changes that can spur productivity in the long run. Furthermore, it makes it very difficult to assess the adequacy of policy in the first place; we do not even know what works and what does not.

Take the ‘levelling up’ agenda, for example. This agenda has been at the centre of government policy until very recently. At its core, the ‘levelling up’ agenda concerns itself with reducing regional disparities by fostering investment, productivity, and growth in the UK’s poorer, least productive regions. Given the country’s deep regional inequalities and their role in hampering aggregate productivity growth, many economists and commentators welcomed the government’s focus on this issue. By scrapping the top income tax rate, the recent’ mini budget’ seems less concerned with inequalities. Where this would leave the ‘levelling up’ agenda remains unclear. As noted in the independent assessment by NIESR, the danger with the government growth plan is that it would primarily benefit the most affluent areas, thus deepening the disparities instead of ‘levelling up’ the poorer regions in the country. The ‘levelling up’ agenda is a good example of a policy that requires long term commitment. Ideally, the institutional set-up should enable a maintained focus on the issue and help foster political consensus so that the long-term structural policies needed are not subject to the whim of the electoral cycle.