The £41.2bn Deficit Explained: What It Means for the UK's Autumn 2025 Budget

Ahead of the planned Autumn Budget, which will take place on 26 November, much of the economic debate will focus on the measures the Chancellor will need to take to meet her fiscal rules and address any budget deficit in 2029-30. In our latest blog, Deputy Director, Stephen Millard, asked Senior Economist Benjamin Caswell to talk through NIESR’s latest forecast and what it may mean for the choices facing the Chancellor in November.

Where do you think the Government’s current spending relative to revenue will be in 2029-30 and where does this number come from?

In our latest forecast, we project that the current budget deficit will be £41.2 billion in 2029-30. This number differs markedly from the OBR’s March 2025 forecast for a few key reasons.

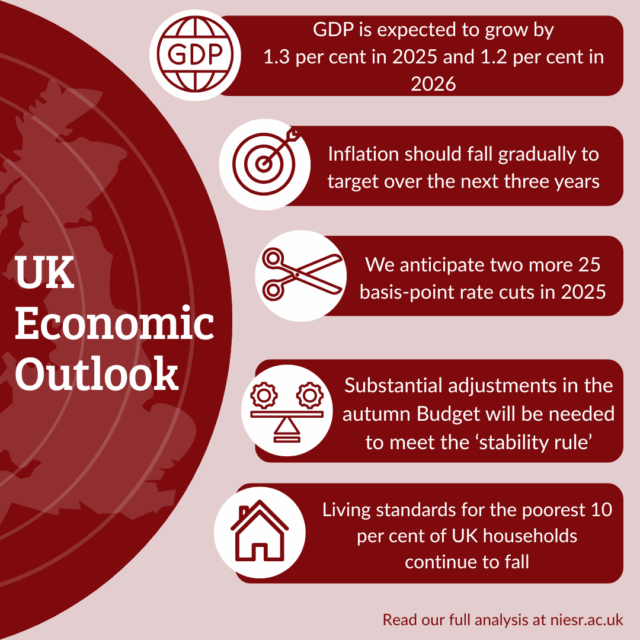

While announced spending paths for the government are taken as given, our UK economic forecast has much weaker economic growth over the next five years. Specifically, our forecast for GDP growth averages 1.2 per cent, while that of the OBR averages 1.7 per cent, over the next 5 years. This means a significantly smaller economic pie at the end of the forecast horizon and additional borrowing to make up the difference between planned expenditure and expected tax revenues.

In addition, we also anticipate higher unemployment and inflation relative to the OBR’s forecast and therefore expect higher spending on welfare payments over the lifetime of the parliament.

What would you advise the Chancellor to do in her forthcoming budget in order to close this deficit?

We should first note that it is the OBR’s forecast that determines what the Chancellor has to do to meet her fiscal rules (not NIESR’s forecast). That said, it seems clear that the Chancellor cannot simultaneously meet her fiscal rules, fulfil spending commitments, and uphold the manifesto promises to avoid tax rises for working people.

Amending the fiscal rules to allow additional borrowing is not politically feasible at present, and financial markets would likely view such a move unfavourably, given that the rules were revised less than one year ago.

This means that this year’s Autumn Budget will require a combination of tax rises and spending cuts to restore fiscal discipline and confidence. Moreover, if the OBR were to forecast a current budget deficit as large as we are currently forecasting (or if the Chancellor wishes to establish a much larger buffer of fiscal headroom), it is likely that the Government will have to look at raising one of the big three taxes: VAT, National Insurance or income tax in the near future.

This will be unpopular as it breaks the manifesto pledge, but it is the only pragmatic way in which the Government can stabilise the outlook for public finances in the medium term.

Beyond the immediate Budget, what principles should guide the design of the fiscal rules, and when would it be palatable to consider reforming the current rules?

There is no perfect set of fiscal rules. However, this does not mean that the existing rules are optimal. In my view, any set of fiscal rules should meet three criteria.

- They should be easy to understand

- They should ensure that debt as a share of GDP cannot grow unbounded

- The binding target should be a stock variable, not a flow.

However, a more palatable moment for reform would be after fiscal credibility has been re-built under the current set of rules. The immediate focus should be on demonstrating discipline to the financial markets by meeting the existing set of self-imposed rules.

At a later stage, a shift towards a framework that meets the above criteria and supports public investment would be more appropriate. However, this is likely to fall within the next parliament.