What next for Quantitative Tightening?

Next Thursday, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee will set the pace of quantitative tightening, or “QT”, for the year ahead. Markets expect the Bank to slow down the process. Would that be the right call?

In this blog, we first explain what QT is and the strategy the Bank has been following. We then consider what impact QT has on the economy and how confident we can be about those effects. Finally, we weigh the arguments for and against a change of course now.

What is QT?

QT or Quantitative Tightening is the process by which central banks like the Bank of England unwind the extraordinary amount of money they injected into the economy in recent years to cushion the effects of shocks such as the Global Financial Crisis, the Brexit referendum, and the Covid-19 pandemic.

To understand QT, it helps to go back to QE. Quantitative Easing was used when the Bank’s policy rate was already near zero and couldn’t be cut further to support the economy. The Bank created new money to buy gilts (UK government bonds) from financial institutions like pension funds and insurers. This extra demand pushed up gilt prices, lowering their yields, and in turn eased borrowing conditions across the economy.

QT is the reverse: instead of adding gilts to its balance sheet, the Bank is now allowing them to mature or selling them back into the market – extinguishing the money created in the first place.

So why is the Bank doing this? At first glance, you might think the aim would be to tighten monetary conditions — and indeed, some central banks, like the Federal Reserve, frame QT partly in this way. But the Bank of England insists otherwise: for them, Bank Rate is the instrument for setting the stance of monetary policy.

Instead, the stated purpose of the Bank’s QT is to rebuild space to use QE again in a future crisis. Without QT, the Bank’s balance sheet would ratchet ever upwards — expanding in bad times but never shrinking in good times. The idea is to make QE genuinely countercyclical: providing support when necessary, and being unwound once conditions allow. Of course, this rationale only really bites if you believe QE will remain a core part of the Bank’s toolkit – let’s come back to that one another time.

What’s less often emphasised is the political economy dimension. QT is not just technical plumbing. The size of the public deficit, the debt-to-GDP ratio, and the government’s fiscal headroom are all now directly affected by Bank of England decisions about its balance sheet. That puts the Bank in a quasi-fiscal role — and it’s not a comfortable place for an independent central bank to be. The more its decisions shape the government’s fiscal position, the harder it becomes to draw a clear line between monetary and fiscal policy, and the more questions arise about the merits of independence. Hence the Bank being very keen to exit from this position.

What impact is QT having on the economy?

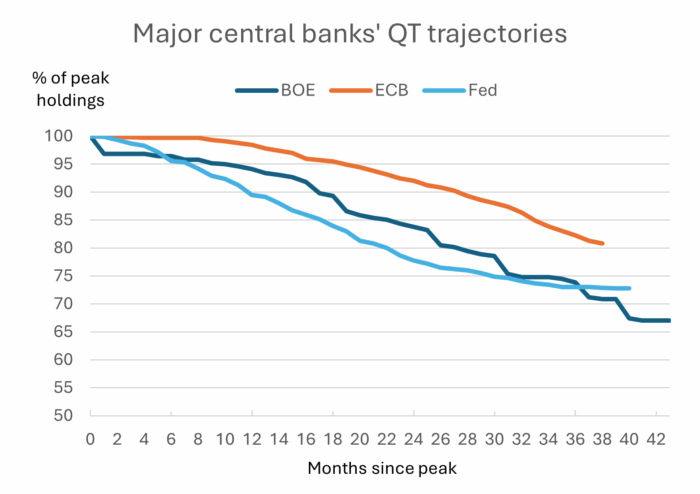

The figure below shows the path of QT in recent years. Since 2022 the Bank has reduced gilt holdings of the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) by around £300 billion (around 30-35% lower than the peak), extinguishing the money created to buy them in the first place. In international terms, the overall pace is broadly comparable to peers, though the BoE has stood out for using active sales, whereas the Fed and ECB have leaned more on passive run-off.

Source: Bank of England – Weekly stock of holdings of gilts by the APF (here); Fed – Securities held outright, including Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities (here and here); ECB – Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) and public sector purchase programme (PSPP) (here).

The design has been gradual and predictable to limit market disruption. And on that metric it has worked well: we haven’t seen the sort of plumbing stress that hit the US money markets in 2019.

But gilt yields have still risen sharply over the past couple of years, with the UK now paying the highest rate to borrow among advanced economies. Much of that reflects a higher “term premium” – the extra compensation investors demand for lending to the UK government for longer maturities. Some commentators have blamed QT for this. Is that fair?

Janet Yellen once said QT would be “like watching paint dry.” And compared to QE, that might be right: it is likely to work through a narrower set of channels and with more muted effects. QE was rolled out during episodes of market stress and, at least initially, came as a surprise — that’s when its impact was strongest. QT, by contrast, has been deliberately predictable and slow-moving.

The main channel is the so-called “portfolio balance” channel. Central banks are price-insensitive buyers: when the Bank of England was expanding the APF, it would buy gilts regardless of price, supporting valuations and compressing yields. As the Bank unwinds its holdings, those gilts must now be absorbed by investors who are more price-sensitive and who demand compensation for taking on duration risk. That shift puts upward pressure on yields.

At its peak, the Bank via the APF held around a third of the entire gilt market; today it is closer to a fifth. When such a large player moves from being a one-way buyer to a steady seller, it is likely to move yields by a non-trivial amount.

So how big are the effects? Most academic studies try to answer this using event studies — looking at yield movements in narrow windows around QT policy announcements or bond sales. There are several problems with this approach. Most studies use US data, but the US Treasury market is far deeper and more liquid than gilts, so impacts in the UK may be larger. And it is hard to find genuine shocks: many QT decisions are well flagged, meaning effects are often priced in already, biasing the estimates downward.

One prominent international study finds that the largest cumulative effects of QT have been in the UK, which is responsible for government bond yields being 44–70 basis points higher across horizons of one year and longer. The reason is the UK has relied more heavily on active sales, which the authors find have a larger market impact than passive roll-off.

That is well above the BoE’s latest of 15–25bps, and the 20bps estimated by Bank staffers last year. It’s worth noting that the Bank’s own internal estimates have been drifting up over time: from <10bps in 2023, to 10–20bps in 2024, to 15–25bps today.

At a minimum, there is a wide band of uncertainty around the true effect of QT on yields — and it’s hard to reject the hypothesis that the effects could be material.

What should the MPC do?

The Bank’s current approach, set in September 2024, is to reduce the stock of UK government bonds held for monetary policy purposes by £100bn over the year to September 2025. Markets widely expect the pace to be slowed from here. What should the MPC do?

One way to think about this is to ask what an optimal policy would look like. Suppose we had a benevolent social planner, taking joined-up decisions on behalf of the country. Faced with even the possibility of bringing down gilt yields by slowing QT, it’s pretty clear would do so. The benefits would surely outweigh the costs associated with the BoE carrying a slightly larger balance sheet for a while.

The argument for pausing is strengthened when you look at the maturity profile of gilts in the APF. Over the next 12 months, far fewer gilts will mature than in the past year. In 2024/25, the balance was almost 90% passive maturities and only 10% active sales. To keep QT at £100bn through to September 2026 would instead require roughly £50bn of active sales. That would put much more pressure directly on the market, with potentially substantial yield effects.

But we don’t have a social planner — we have an independent MPC, bound by its remit. The 2024 remit letter is clear:

“The Committee may judge it necessary to unwind any unconventional policy instruments, consistent with the requirements of this remit, for monetary policy purposes.” (My emphasis)

How, then, could the MPC justify a pause or slowdown? The answer I think lies in the secondary objective. The Bank’s primary goal is price stability. But subject to that, it is also the government’s economic policy — which includes “supporting investment through the effective management of public finances and overseeing sustainable taxes and borrowing, to deliver long-term growth…”

Seen in this light, the case for halting active QT can be framed as:

- No cost to the primary objective: Bank Rate is the main policy tool, and sufficient headroom for future QE has already been restored.

- Supporting the secondary objective: slowing active QT supports orderly markets and helps manage financing costs, in line with government economic policy.

Of course, some would see this as a slippery slope: once QT is adjusted to ease fiscal pressures, where does it stop? That might be right — but there is at least a clear safeguard in the MPC’s remit: the primary objective of delivering price stability always takes precedence. So the MPC cannot take actions to support the secondary objective if in its judgement these would compromise price stability.

To conclude, the challenge for the MPC is that it likes to think it can operate in a monetary vacuum. But because its past decisions have swollen the balance sheet to such an extent, its decisions on QT cannot be made independently of fiscal realities. QT now has to be managed in a way that respects those constraints.